Thu, Apr 18, 2024

Volume 1, Issue 1 (6-2015)

Iran J Neurosurg 2015, 1(1): 23-27 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Azimi P, Mohammadi H, Nayeb-Aghaei H, Azhari S, Safdari-Ghandehari H, Sadeghi S. Functionality Status and Surgical Outcome of Fenestration versus Laminotomy Discectomy in Patients with Lumbar Disc Herniation. Iran J Neurosurg 2015; 1 (1) :23-27

URL: http://irjns.org/article-1-2-en.html

URL: http://irjns.org/article-1-2-en.html

Parisa Azimi *

1, Hassan-Reza Mohammadi

1, Hassan-Reza Mohammadi

, Hossein Nayeb-Aghaei

, Hossein Nayeb-Aghaei

, Shirzad Azhari

, Shirzad Azhari

, Hossein Safdari-Ghandehari

, Hossein Safdari-Ghandehari

, Sohrab Sadeghi

, Sohrab Sadeghi

1, Hassan-Reza Mohammadi

1, Hassan-Reza Mohammadi

, Hossein Nayeb-Aghaei

, Hossein Nayeb-Aghaei

, Shirzad Azhari

, Shirzad Azhari

, Hossein Safdari-Ghandehari

, Hossein Safdari-Ghandehari

, Sohrab Sadeghi

, Sohrab Sadeghi

Full Text [PDF 503 kb]

(2954 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5927 Views)

Full Text: (1575 Views)

Introduction

Low back pain is the most common type of back pain (1), mainly caused by lumbar disc herniation (LDH). The term LDH refers to the nucleus in the center of the disc pushes out of its normal space (2). Symptoms for LDH include back and leg pain, which may spread out into the hand (3). There are several tools for measuring the performance status or functionality in patients with low back pain that it can be judged to make appropriate informed clinical decisions. In 1998 an international group designed the Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) to assess pain, function, well-being, disability, and satisfaction for evaluating the treatment for low back pain (4). It has been validated as an outcome tool in low back pain in Iran (5).

The treatment of LDH is the most controversial topic in the spine literature, as to whether surgical treatment should be attempted and if so which surgical approach is optimal (6). Open discectomy as fenestration and laminotomy discectomy is the standard procedure for symptomatic LDH and it involves removal of the portion of the intervertebral disc compressing the nerve root or spinal cord (or both) (7). The question is whether there are any differences in the methods of approach according to surgery outcomes. Thus, the aim of this study was to compare the outcomes of fenestration discectomy versus laminotomy discectomy for LDH based on COMI and ODI over at least 2 year follow-up.

Methods and Materials

Patients and Data Collection

This was retrospective and cross-sectional study. Between January 2007 and April 2012, patients with a single-level disc herniation were attended to the neurosurgery clinic of Imam-Hossain Hospital a large teaching hospital in Tehran, Iran and were selected to undergo fenestration discectomy or laminotomy discectomy. After at least 6 weeks of conservative therapy, patients who had persistent radiculopathy and positive tension signs in both straight- and crossed- leg raising tests with absence of correlative neurological deficits were included. There were no restrictions on patient selection with regard to types of LDH, age or other characteristics. Patients who had lateral or central stenosis of spinal canal, previous surgery, drug dependency, severe degenerative narrowing of the disc space at the index level, and cauda equina syndrome were excluded.

The fenestration discectomy or laminotomy discectomy was performed in a standard fashion (7), by five surgeons with National Board certification and senior resident in the presence of professors. Fenestration was performed for patients with lateral disc and with or without extruded fragments and laminotomy was performed for patients with large central or paracentral disc herniations. Patients were assessed pre- and post-operatively at last follow-up based on COMI and ODI measures and and ODI measures and the fenestration discectomy (n=45) or laminotomy discectomy (n=63) groups were compared. The MacNab scale was used to determine the clinical outcome after surgery (8). The state of satisfaction was graded as excellent, good, fair or poor.

Surgical Procedures

In laminotomy discectomy, the whole or half portion of the lamina was removed respectively along with overlying ligaments. In fenestration, the lamina was removed partially whenever needed, and the herniated fragment was removed after retracting the nerve roots. The remaining nucleus in the disc space was preserved as much as possible. Free fat grafts were sited over the root and the dura at the end of each method to prevent excessive adhesion (7). In all 39 of 108 cases, the microscope was applied for discectomy.

The Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) questionnaire

The Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) is a short, self-administered and multidimensional outcome instrument. It consists of 5 subscale including 7 questions that evaluate pain (2 items), function (1 item), well-being (1 item), disability (2 items) and satisfaction (1items). The pain score (the highest value out of leg pain and back pain; already scored 0–10) was calculated. For the other items, that scored 1–5 [function, symptom-specific well-being, general well-being, disability (average of social and work disability)] were first re-scored on a 0–10 scale (raw score -1, multiplied by 2.5). The COMI summary score, ranging from 0 (best health status) to 10 (worst health status) is then calculated by averaging the values for the 5 subscales (worst pain, function, symptom-specific well-being, general well-being, and disability). The satisfaction subscale was computed for assessment of treatment outcome (Table 1) (4, 9).

Low back pain is the most common type of back pain (1), mainly caused by lumbar disc herniation (LDH). The term LDH refers to the nucleus in the center of the disc pushes out of its normal space (2). Symptoms for LDH include back and leg pain, which may spread out into the hand (3). There are several tools for measuring the performance status or functionality in patients with low back pain that it can be judged to make appropriate informed clinical decisions. In 1998 an international group designed the Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) to assess pain, function, well-being, disability, and satisfaction for evaluating the treatment for low back pain (4). It has been validated as an outcome tool in low back pain in Iran (5).

The treatment of LDH is the most controversial topic in the spine literature, as to whether surgical treatment should be attempted and if so which surgical approach is optimal (6). Open discectomy as fenestration and laminotomy discectomy is the standard procedure for symptomatic LDH and it involves removal of the portion of the intervertebral disc compressing the nerve root or spinal cord (or both) (7). The question is whether there are any differences in the methods of approach according to surgery outcomes. Thus, the aim of this study was to compare the outcomes of fenestration discectomy versus laminotomy discectomy for LDH based on COMI and ODI over at least 2 year follow-up.

Methods and Materials

Patients and Data Collection

This was retrospective and cross-sectional study. Between January 2007 and April 2012, patients with a single-level disc herniation were attended to the neurosurgery clinic of Imam-Hossain Hospital a large teaching hospital in Tehran, Iran and were selected to undergo fenestration discectomy or laminotomy discectomy. After at least 6 weeks of conservative therapy, patients who had persistent radiculopathy and positive tension signs in both straight- and crossed- leg raising tests with absence of correlative neurological deficits were included. There were no restrictions on patient selection with regard to types of LDH, age or other characteristics. Patients who had lateral or central stenosis of spinal canal, previous surgery, drug dependency, severe degenerative narrowing of the disc space at the index level, and cauda equina syndrome were excluded.

The fenestration discectomy or laminotomy discectomy was performed in a standard fashion (7), by five surgeons with National Board certification and senior resident in the presence of professors. Fenestration was performed for patients with lateral disc and with or without extruded fragments and laminotomy was performed for patients with large central or paracentral disc herniations. Patients were assessed pre- and post-operatively at last follow-up based on COMI and ODI measures and and ODI measures and the fenestration discectomy (n=45) or laminotomy discectomy (n=63) groups were compared. The MacNab scale was used to determine the clinical outcome after surgery (8). The state of satisfaction was graded as excellent, good, fair or poor.

Surgical Procedures

In laminotomy discectomy, the whole or half portion of the lamina was removed respectively along with overlying ligaments. In fenestration, the lamina was removed partially whenever needed, and the herniated fragment was removed after retracting the nerve roots. The remaining nucleus in the disc space was preserved as much as possible. Free fat grafts were sited over the root and the dura at the end of each method to prevent excessive adhesion (7). In all 39 of 108 cases, the microscope was applied for discectomy.

The Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) questionnaire

The Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) is a short, self-administered and multidimensional outcome instrument. It consists of 5 subscale including 7 questions that evaluate pain (2 items), function (1 item), well-being (1 item), disability (2 items) and satisfaction (1items). The pain score (the highest value out of leg pain and back pain; already scored 0–10) was calculated. For the other items, that scored 1–5 [function, symptom-specific well-being, general well-being, disability (average of social and work disability)] were first re-scored on a 0–10 scale (raw score -1, multiplied by 2.5). The COMI summary score, ranging from 0 (best health status) to 10 (worst health status) is then calculated by averaging the values for the 5 subscales (worst pain, function, symptom-specific well-being, general well-being, and disability). The satisfaction subscale was computed for assessment of treatment outcome (Table 1) (4, 9).

The Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) questionnaire

The Iranian version of Oswestry Disability Index (ODI): This is a measure of functionality and contains 10 items. The possible score on the ODI ranges from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicating worst conditions. The psychometric properties of Iranian version of questionnaire are well documented (10).

Statistical Analysis

For parameters describing the patient population, continuous variables were compared. Since the data were normally distributed T-test was used. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson Chi-square test.

In addition, Pearson coefficient test was used for calculating the correlation between ODI and COMI in patients with LDH. Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS for windows, ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was assumed as p<0.05.

Ethics

The Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences approved the study.

Results

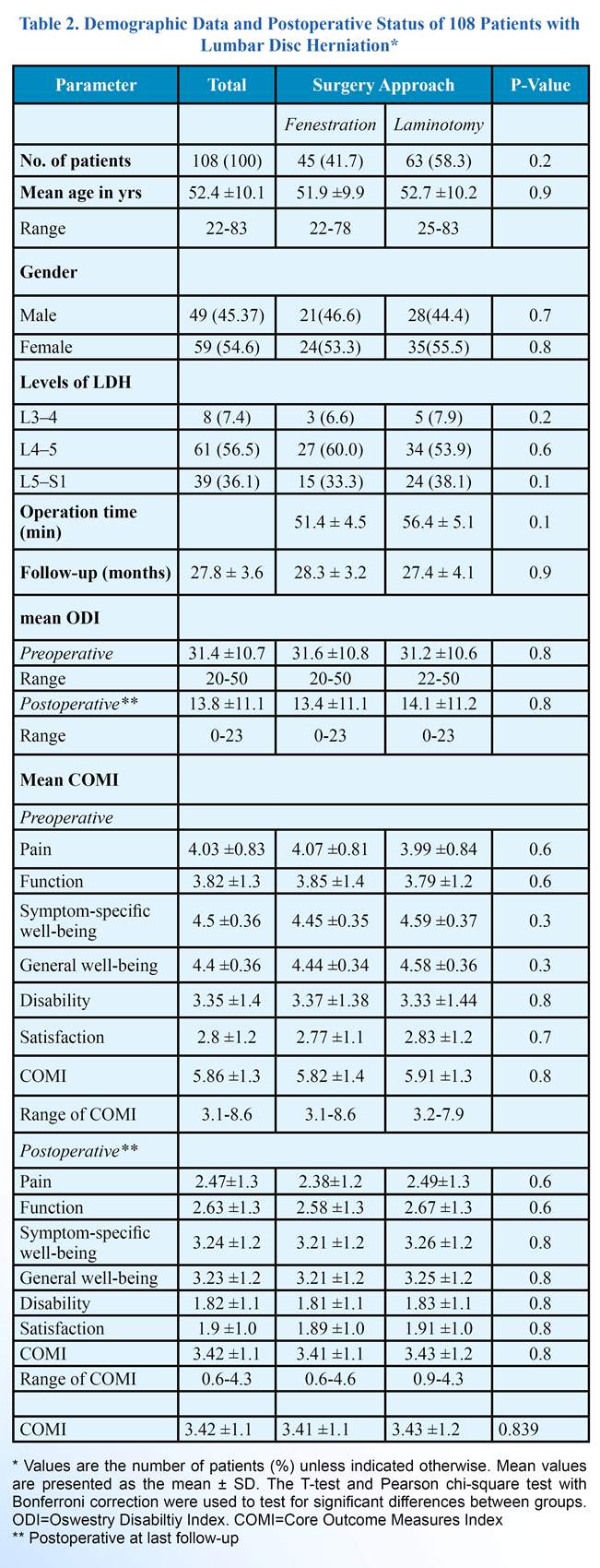

In all, 108 patients completed the study. The characteristics of patients and their scores on the COMI, the ODI and affected levels are shown in Table 2.

The demographic distribution of both groups was similar. The mean clinical follow-up was 27.8 (SD=3.6) months (ranging from 24 to 37 months). The demographic distribution of both groups was similar. There was no significant difference in the operation time and blood loss between fenestration and laminotomy discectomy groups. In addition, no significant difference was observed between two groups based on involvement levels (Table 2).

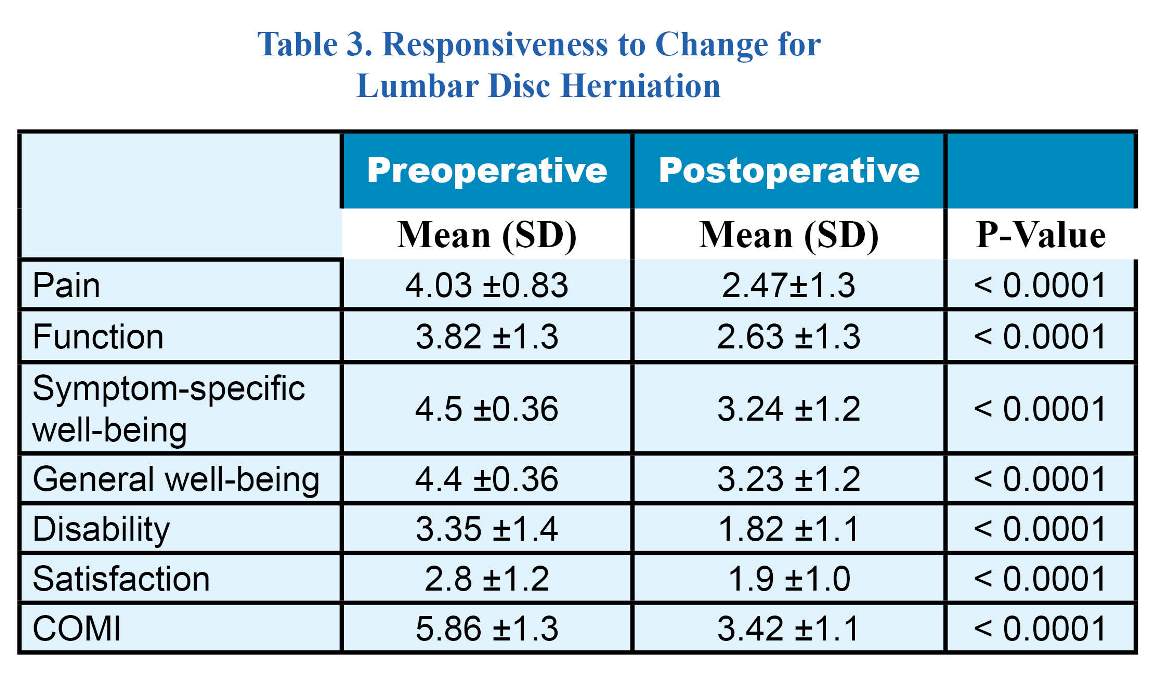

There was no significant difference in preoperative COMI score and the ODI between fenestration and laminotomy discectomy groups. However, in all instances the COMI was able to detect changes after intervention (surgery) indicating improvements in all subscales. The results are shown in Table 3.

The ODI score also was found to be statistically different between the groups in pre-and postoperative (P<0.0001). The change in the ODI correlated strongly with change in the COMI lending support to its good convergent validity (r=0.79; P<0.001) for patients with LDH.

Based on Macnab’s criteria, “Excellent”, “Good”, “Fair” and “Poor” outcome were seen in 32 (71.1%), 10 (22.2%), 2 (4.4%), and in 1 case (2.2%) for fenestration and 43 (68.3%), 14 (22.2%), 4 (6.3%) and in 2 cases (3.1%) for laminotomy discectomy, respectively.

Two patients (3.2%) within laminotomy group had recurrent disk herniations and underwent reoperation; however, it was not observed in fenestration group. No case was observed with missed level surgery. Cauda-equina syndrome occurred in 1 case (0.9%) in laminotomy group; however, it was not observed in fenestration group. In 1 case (1.6%) within laminotomy group dural laceration occurred during surgery which were repaired and no one showed CSF leakage or meningitis. No mortality rate was observed due to surgery.

The Iranian version of Oswestry Disability Index (ODI): This is a measure of functionality and contains 10 items. The possible score on the ODI ranges from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicating worst conditions. The psychometric properties of Iranian version of questionnaire are well documented (10).

Statistical Analysis

For parameters describing the patient population, continuous variables were compared. Since the data were normally distributed T-test was used. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson Chi-square test.

In addition, Pearson coefficient test was used for calculating the correlation between ODI and COMI in patients with LDH. Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS for windows, ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was assumed as p<0.05.

Ethics

The Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences approved the study.

Results

In all, 108 patients completed the study. The characteristics of patients and their scores on the COMI, the ODI and affected levels are shown in Table 2.

The demographic distribution of both groups was similar. The mean clinical follow-up was 27.8 (SD=3.6) months (ranging from 24 to 37 months). The demographic distribution of both groups was similar. There was no significant difference in the operation time and blood loss between fenestration and laminotomy discectomy groups. In addition, no significant difference was observed between two groups based on involvement levels (Table 2).

There was no significant difference in preoperative COMI score and the ODI between fenestration and laminotomy discectomy groups. However, in all instances the COMI was able to detect changes after intervention (surgery) indicating improvements in all subscales. The results are shown in Table 3.

The ODI score also was found to be statistically different between the groups in pre-and postoperative (P<0.0001). The change in the ODI correlated strongly with change in the COMI lending support to its good convergent validity (r=0.79; P<0.001) for patients with LDH.

Based on Macnab’s criteria, “Excellent”, “Good”, “Fair” and “Poor” outcome were seen in 32 (71.1%), 10 (22.2%), 2 (4.4%), and in 1 case (2.2%) for fenestration and 43 (68.3%), 14 (22.2%), 4 (6.3%) and in 2 cases (3.1%) for laminotomy discectomy, respectively.

Two patients (3.2%) within laminotomy group had recurrent disk herniations and underwent reoperation; however, it was not observed in fenestration group. No case was observed with missed level surgery. Cauda-equina syndrome occurred in 1 case (0.9%) in laminotomy group; however, it was not observed in fenestration group. In 1 case (1.6%) within laminotomy group dural laceration occurred during surgery which were repaired and no one showed CSF leakage or meningitis. No mortality rate was observed due to surgery.

Discussion

This is the first study about open discectomy outcomes based on the COMI in the literature over at least 2 year follow-up. The improvement in the COMI and ODI scores in both groups were significant. Both techniques were equally effective in surgical outcomes by reducing the tension on the nerve root caused by the herniated disc. The success rate of lumbar discectomy is about 70 to 90% (11,12). Most studies on microdiscectomy and percutaneous discectomies report a surgical time of 40 to 120 minutes (13-15). These results are consistent with our findings in both groups. The change in the ODI good correlated with change in the COMI as in the study by Lozano-Álvarez et al. (r=0.73; P<0.01) (16), and Deyo et al. (r = 0.60; P<0.01) (3). In this study also this issue was observed. In addition, the ODI improved in two groups after surgery in last follow-up. The mortality rate for a lumbar laminectomy is between 0.8% and 1% (17). However, in this study no mortality rate was observed. The results of the current study showed that no statistical difference between two methods based on outcomes. However, best outcome were reported after fenestration with other studies (17,18). Albeit, different assessment tools are not standardized, which makes it difficult to compare results of studies. The COMI can assess pain, function, well-being, disability, and satisfaction that may be a comprehensive tool for evaluating the treatment in low back pain. In addition, it is a quick and effective alternative in daily clinical practice to evaluate the condition of patients (5). However, it seems that a more comprehensive tool is required.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the most common method of pain evaluation is visual analogue score (VAS) that we did not use it. Secondly, the sample size was small and a larger study population is very essential. In addition, larger groups of patients with longer follow-up are needed to confirm these results. Thirdly, the study was not double blind and a prospective randomized study, so future studies are recommended to consider these issues. Fourthly, job and literacy level for filling questionnaires and similar physical status in two groups could make the results more acceptable and future studies are required

to assess this issue. Fifthly, we cannot study medical responses as back pain and radicular pain separately. Sixthly, other associated diseases such as diabetes mellitus were not assessed, and also days of hospitalization in two groups were not evaluated.

Finally, we cannot study primary outcomes as 1. Sciatica-specific outcomes: the Sciatica Bothersomeness Index (SBI) and the Sciatica Frequency Index (SFI) (19); 2. Remained/persisted neurological deficit of lower extremity or bowel/urinary incontinence; 3. Functional outcome including, daily activity and return to work; and secondary outcomes as 1. The following common complications of surgery: i) Thromboembolic complications; ii) Procedure-related complications; iii) Re-hospitalization due to other causes except recurrence of discopathy; iv) Surgical re-intervention; and 2. Opioid use.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that fenestration or laminotomy discectomy are an efficacious procedure for treatment of LDH. However, both methods are equally effective in surgical outcome and functionality status.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Neurosurgery Ward of Imam-Hossein Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

Funding

None declared.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

This is the first study about open discectomy outcomes based on the COMI in the literature over at least 2 year follow-up. The improvement in the COMI and ODI scores in both groups were significant. Both techniques were equally effective in surgical outcomes by reducing the tension on the nerve root caused by the herniated disc. The success rate of lumbar discectomy is about 70 to 90% (11,12). Most studies on microdiscectomy and percutaneous discectomies report a surgical time of 40 to 120 minutes (13-15). These results are consistent with our findings in both groups. The change in the ODI good correlated with change in the COMI as in the study by Lozano-Álvarez et al. (r=0.73; P<0.01) (16), and Deyo et al. (r = 0.60; P<0.01) (3). In this study also this issue was observed. In addition, the ODI improved in two groups after surgery in last follow-up. The mortality rate for a lumbar laminectomy is between 0.8% and 1% (17). However, in this study no mortality rate was observed. The results of the current study showed that no statistical difference between two methods based on outcomes. However, best outcome were reported after fenestration with other studies (17,18). Albeit, different assessment tools are not standardized, which makes it difficult to compare results of studies. The COMI can assess pain, function, well-being, disability, and satisfaction that may be a comprehensive tool for evaluating the treatment in low back pain. In addition, it is a quick and effective alternative in daily clinical practice to evaluate the condition of patients (5). However, it seems that a more comprehensive tool is required.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the most common method of pain evaluation is visual analogue score (VAS) that we did not use it. Secondly, the sample size was small and a larger study population is very essential. In addition, larger groups of patients with longer follow-up are needed to confirm these results. Thirdly, the study was not double blind and a prospective randomized study, so future studies are recommended to consider these issues. Fourthly, job and literacy level for filling questionnaires and similar physical status in two groups could make the results more acceptable and future studies are required

to assess this issue. Fifthly, we cannot study medical responses as back pain and radicular pain separately. Sixthly, other associated diseases such as diabetes mellitus were not assessed, and also days of hospitalization in two groups were not evaluated.

Finally, we cannot study primary outcomes as 1. Sciatica-specific outcomes: the Sciatica Bothersomeness Index (SBI) and the Sciatica Frequency Index (SFI) (19); 2. Remained/persisted neurological deficit of lower extremity or bowel/urinary incontinence; 3. Functional outcome including, daily activity and return to work; and secondary outcomes as 1. The following common complications of surgery: i) Thromboembolic complications; ii) Procedure-related complications; iii) Re-hospitalization due to other causes except recurrence of discopathy; iv) Surgical re-intervention; and 2. Opioid use.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that fenestration or laminotomy discectomy are an efficacious procedure for treatment of LDH. However, both methods are equally effective in surgical outcome and functionality status.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Neurosurgery Ward of Imam-Hossein Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

Funding

None declared.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Kordi R, Rostami M. Low back pain in children and adolescents: an algorithmic clinical approach. Iran J Pediatr. 2011;21(3):259-70.

- Li Y, Fredrickson V, Resnick DK. How Should We Grade Lumbar Disc Herniation and Nerve Root Compression? A Systematic Review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 May 14. [Epub ahead of print]

- Fardon DF, Milette PC. Nomenclature and classification of lumbar disc pathology: recommendations of the Combined Task Forces of the North American Spine Society, American Society of Spine Radiology, and American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine. 2001;26(5):E93-E113.

- Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, et al. Outcome measures for low back pain research. A proposal for standardized use. Spine. 1998;23(18):2003-13.

- Mohammadi HR, Azimi P, Zali AR, et al. An outcome measure of functionality and pain in patients with low back disorder: a validation study of the Iranian version of Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI). Asian J Neurosurg 2014 [Epub ahead of print].

- Padua R, Padua S. Romanini E. Ten to 15 year outcome of surgery for lumbar disc hemiations: radiographic instability and clinical fndings. Eur Spine J. 1999;8(1):70-4.

- Garg B, Nagraja UB, Jayaswal A. Microendoscopic versus open discectomy for lumbar disc herniation: a prospective randomised study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2011;19(1):30-4.

- Akbar A, Mahar A. Lumbar disc prolapse: management and outcome analysis of 96 surgically treated patients.. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52(2):62-5.

- Mannion AF, Porchet F, Kleinstück FS, et al. The quality of spine surgery from the patient’s perspective. Part 1: the Core Outcome Measures Index in clinical practice. Eur Spine J. 2009;18 Suppl 3:367-73.

- Mousavi SJ, Parnianpour M, Mehdian H, et al. The Oswestry Disability Index, the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale: translation and validation studies of the Iranian versions. Spine. 2006;31(14):E454-9.

- Kahanovitz N, Viola K, McCulloch J. Limited surgical discectomy and microdiscectomy. A clinical comparison. Spine. 1989;14(1):79-81.

- Spengler DM. Lumbar discectomy. Results with limited disc excision and selective foraminotomy. Spine. 1982;7(6):604-7.

- Mayer HM, Brock M. Percutaneous endoscopic discectomy: surgical technique and preliminary results compared to microsurgical discectomy. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(2):216-25.

- Stolke D, Sollmann WP, Seifert V. Intra- and postoperative complications in lumbar disc surgery. Spine. 1989;14(1):56-9.

- Lew SM, Mehalic TF, Fagone KL. Transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic discectomy in the treatment of far-lateral and foraminal lumbar disc herniations. J Neurosurg. 2001;94 (2 Suppl):216-20.

- WHO: Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. [Available from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/]

- Tabatabaei SM, Seddighi AS, Seddighi A, et al. Clinical Results of 30 Years Surgery On 2026 Patients with Lumbar Disc Herniation. WScJ. 2012;3: 80-86.

- Lakicević G1, Ostojić L, Splavski B, et al. Comparative outcome analyses of differently surgical approaches to lumbar disc herniation. Coll Antropol. 2009;33 Suppl 2:79-84.

- Grøvle L, Haugen AJ, Keller A, Natvig B, Brox JI, Grotle M. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Norwegian versions of the Maine-Seattle Back Questionnaire and the Sciatica Bothersomeness and Frequency Indices. Spine . 2008;33(21):2347-53.

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Gamma Knife Radiosurgery

References

1. Kordi R, Rostami M. Low back pain in children and adolescents: an algorithmic clinical approach. Iran J Pediatr. 2011;21(3):259-70. [PMID] [PMCID]

2. Li Y, Fredrickson V, Resnick DK. How Should We Grade Lumbar Disc Herniation and Nerve Root Compression? A Systematic Review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 May 14. [Epub ahead of print]

3. Fardon DF, Milette PC. Nomenclature and classification of lumbar disc pathology: recommendations of the Combined Task Forces of the North American Spine Society, American Society of Spine Radiology, and American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine. 2001;26(5):E93-E113. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-200103010-00006] [PMID]

4. Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, et al. Outcome measures for low back pain research. A proposal for standardized use. Spine. 1998;23(18):2003-13. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-199809150-00018] [PMID]

5. Mohammadi HR, Azimi P, Zali AR, et al. An outcome measure of functionality and pain in patients with low back disorder: a validation study of the Iranian version of Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI). Asian J Neurosurg 2014 [Epub ahead of print].

6. Padua R, Padua S. Romanini E. Ten to 15 year outcome of surgery for lumbar disc hemiations: radiographic instability and clinical fndings. Eur Spine J. 1999;8(1):70-4. [DOI:10.1007/s005860050129] [PMID] [PMCID]

7. Garg B, Nagraja UB, Jayaswal A. Microendoscopic versus open discectomy for lumbar disc herniation: a prospective randomised study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2011;19(1):30-4. [DOI:10.1177/230949901101900107] [PMID]

8. Akbar A, Mahar A. Lumbar disc prolapse: management and outcome analysis of 96 surgically treated patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52(2):62-5. [PMID]

9. Mannion AF, Porchet F, Kleinstück FS, et al. The quality of spine surgery from the patient's perspective. Part 1: the Core Outcome Measures Index in clinical practice. Eur Spine J. 2009;18 Suppl 3:367-73.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-009-0931-y [DOI:10.1007/s00586-009-0942-8]

10. Mousavi SJ, Parnianpour M, Mehdian H, et al. The Oswestry Disability Index, the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale: translation and validation studies of the Iranian versions. Spine. 2006;31(14):E454-9. [DOI:10.1097/01.brs.0000222141.61424.f7] [PMID]

11. Kahanovitz N, Viola K, McCulloch J. Limited surgical discectomy and microdiscectomy. A clinical comparison. Spine. 1989;14(1):79-81. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-198901000-00016] [PMID]

12. Spengler DM. Lumbar discectomy. Results with limited disc excision and selective foraminotomy. Spine. 1982;7(6):604-7. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-198211000-00015]

13. Mayer HM, Brock M. Percutaneous endoscopic discectomy: surgical technique and preliminary results compared to microsurgical discectomy. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(2):216-25. [DOI:10.3171/jns.1993.78.2.0216] [PMID]

14. Stolke D, Sollmann WP, Seifert V. Intra- and postoperative complications in lumbar disc surgery. Spine. 1989;14(1):56-9. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-198901000-00011] [PMID]

15. Lew SM, Mehalic TF, Fagone KL. Transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic discectomy in the treatment of far-lateral and foraminal lumbar disc herniations. J Neurosurg. 2001;94 (2 Suppl):216-20. [PMID]

16. WHO: Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. [Available from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/]

17. Tabatabaei SM, Seddighi AS, Seddighi A, et al. Clinical Results of 30 Years Surgery On 2026 Patients with Lumbar Disc Herniation. WScJ. 2012;3: 80-86.

18. Lakicević G1, Ostojić L, Splavski B, et al. Comparative outcome analyses of differently surgical approaches to lumbar disc herniation. Coll Antropol. 2009;33 Suppl 2:79-84. [PMID]

19. Grøvle L, Haugen AJ, Keller A, Natvig B, Brox JI, Grotle M. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Norwegian versions of the Maine-Seattle Back Questionnaire and the Sciatica Bothersomeness and Frequency Indices. Spine . 2008;33(21):2347-53. [DOI:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818047d6] [PMID]

| Rights and Permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |