Fri, Jun 6, 2025

Volume 10 - Continuous Publishing

Iran J Neurosurg 2024, 10 - Continuous Publishing: 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yadav V, Pandey N, Prasad R S. Subdural Hematoma Hidden by Acute Epidural

Hematoma: The First Report of Two Cases. Iran J Neurosurg 2024; 10 : 25

URL: http://irjns.org/article-1-406-en.html

URL: http://irjns.org/article-1-406-en.html

1- Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. , vikrantyadav473@gmail.com

2- Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India.

2- Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India.

Keywords: Epidural hematoma (EDH), Subdural hematoma (SDH), Glasgow coma scale (GCS), Traumatic brain injury, Computed tomography

Full Text [PDF 2664 kb]

(297 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1078 Views)

Full Text: (14 Views)

1. Introduction

Epidural hematoma (EDH) is an intracranial emergency and extremely lethal if not treated quickly. Judicious surgical evacuation of EDH is one of the most rewarding neurosurgical procedures [1, 2]. Acute subdural hematoma (SDH) is another lethal form of traumatic brain injury (TBI) that has a grave prognosis with high mortality [3, 4]. The coexistence of both of these entities in a patient with TBI leads to a series of events. In most patients, EDH and SDH occur in different positions. Occurrence of both EDH and SDH, on the same side after a single trauma, is extremely rare [5, 6]. Sometimes, the EDH volume compresses the underlying SDH, which in turn leads to radiological obliteration of SDH which then causes misjudgment in the appropriate surgical procedures. Here, the authors present two cases of TBIs in which patients were initially operated on for EDH, but later, postoperative scans revealed SDH on the same side, which was invisible in preoperative scans. The identification of SDH in postoperative scans prompted a second surgery.

2. Cases Presentation

Case 1

A 21-year-old male patient was brought to the emergency room in an unconscious state following a high-velocity road traffic accident. The time interval between the accident and arrival in the emergency room was 8 hours because he was primarily managed in the district hospital. At the time of arrival, the patient was in decerebrate posture. The Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score was 4, blood pressure was 152.94 mm Hg, pulse rate was 56, respiratory rate was 26 per minute and pupils were sluggish and reactive to light. Immediate orotracheal intubation was performed. Routine blood investigations, including the coagulation profile, were normal. Computed tomography (CT) scans revealed a left-sided frontal bone fracture with an underlying giant EDH measuring around 70 mL in volume (Figure 1a).

Epidural hematoma (EDH) is an intracranial emergency and extremely lethal if not treated quickly. Judicious surgical evacuation of EDH is one of the most rewarding neurosurgical procedures [1, 2]. Acute subdural hematoma (SDH) is another lethal form of traumatic brain injury (TBI) that has a grave prognosis with high mortality [3, 4]. The coexistence of both of these entities in a patient with TBI leads to a series of events. In most patients, EDH and SDH occur in different positions. Occurrence of both EDH and SDH, on the same side after a single trauma, is extremely rare [5, 6]. Sometimes, the EDH volume compresses the underlying SDH, which in turn leads to radiological obliteration of SDH which then causes misjudgment in the appropriate surgical procedures. Here, the authors present two cases of TBIs in which patients were initially operated on for EDH, but later, postoperative scans revealed SDH on the same side, which was invisible in preoperative scans. The identification of SDH in postoperative scans prompted a second surgery.

2. Cases Presentation

Case 1

A 21-year-old male patient was brought to the emergency room in an unconscious state following a high-velocity road traffic accident. The time interval between the accident and arrival in the emergency room was 8 hours because he was primarily managed in the district hospital. At the time of arrival, the patient was in decerebrate posture. The Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score was 4, blood pressure was 152.94 mm Hg, pulse rate was 56, respiratory rate was 26 per minute and pupils were sluggish and reactive to light. Immediate orotracheal intubation was performed. Routine blood investigations, including the coagulation profile, were normal. Computed tomography (CT) scans revealed a left-sided frontal bone fracture with an underlying giant EDH measuring around 70 mL in volume (Figure 1a).

The patient was immediately operated on. A left frontal trephine craniectomy was performed with complete evacuation of EDH. The underlying dura was pulsatile and slightly bulging. The patient was supported by a ventilator during the postoperative period. A postoperative CT scan after 2 hours showed mixed density lesion at the same location (Figure 1b). The patient was again taken for surgical evacuation of the hematoma. On re-exploration, the dura was incised and around 50 mL of subdural blood was evacuated (Figures 1c, 1d, and 1e). Postoperative scans indicated complete hematoma evacuation (Figure 1f). The patient remained on the ventilator, failed to recover, and died after 3 days.

Case 2

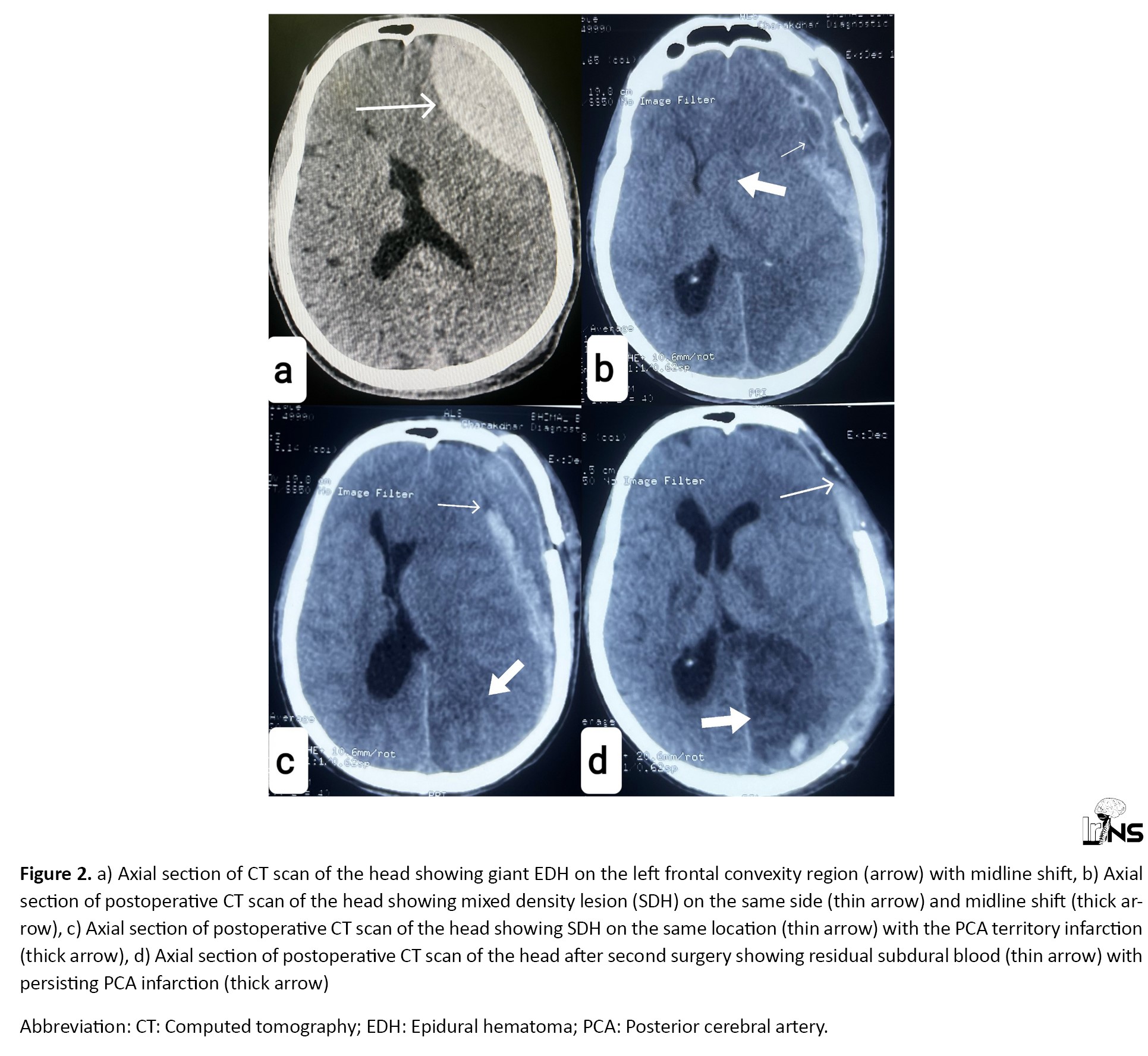

An 18-year-old male patient was brought to the emergency room in an unconscious state following high-velocity trauma due to a physical assault. The time interval between assault and arrival in the emergency room was 24 hours. On arrival, GCS was 8, blood pressure was 140.90 mm Hg, pulse rate was 62, respiratory rate was 23 per minute, and pupils were bilaterally constricted. A CT scan of the head revealed a left-sided giant EDH measuring 60 mL in volume (Figure 2a).

Case 2

An 18-year-old male patient was brought to the emergency room in an unconscious state following high-velocity trauma due to a physical assault. The time interval between assault and arrival in the emergency room was 24 hours. On arrival, GCS was 8, blood pressure was 140.90 mm Hg, pulse rate was 62, respiratory rate was 23 per minute, and pupils were bilaterally constricted. A CT scan of the head revealed a left-sided giant EDH measuring 60 mL in volume (Figure 2a).

Routine blood investigations, including the coagulation profile, were normal. The patient was immediately operated on. A left frontal trephine craniotomy was performed with complete evacuation of EDH. The underlying dura was pulsatile and lax. A postoperative CT scan after 2 hours showed mixed density lesion at the same location with ipsilateral posterior cerebral artery (PCA) territory infarction with midline shift (Figures 2b, and 2c). The patient was immediately operated again. Left frontotemporoparietal craniectomy was performed with SDH evacuation along with lax duraplasty. Postoperative scans showed complete evacuation of the hematoma (Figure 2d). The patient was tracheostomized and kept on the ventilator. The patient’s condition gradually deteriorated and died after 12 days.

3. Discussion

EDHs are fatal types of TBIs if left untreated. Crucial causes leading to the formation of EDH are middle meningeal vessel rupture, stripping of dural veins, fracture bleed, or sinus bleeding [7, 8]. EDH on CT scans appears as a crescentic or biconvex hyperdense lesion in the epidural space [9]. SDH is commonly caused by the rupture of veins that are deep into the dura mater. Acute SDH presents as a hyperdense collection in the subdural space that may be concavo-convex or irregular [5, 9]. In the first case, the cause of EDH was a fracture bleed with stripping of dural veins. In the second case, dural veins stripping with sinus bleed was the probable cause. In both cases, rupture of the deep venous system to the dura mater was the cause of SDH. These entities are easily identifiable on conventional CT scans when occur in different locations in the same patient. Sometimes, it is very difficult to differentiate both SDH from EDH when both occur in the same location, as evident in these two case reports. SDH may be obliterated radiologically, probably due to the large volume of EDH or the redistribution and dispersal of hematoma in subdural spaces [5, 10, 11, 12]. These situations can lead to the non-identification of hematoma in subdural spaces radiologically, which further leads to misjudgment of the appropriate surgical procedures and delay in adequate decompression of the brain. During the redistribution of hematoma, the mixing of cerebrospinal fluid gives SDH a mixed-density appearance [5]. In both reported cases, following the evacuation of EDH, the hematoma in subdural spaces appeared as mixed-density lesions on CT scans (Figures 1b, 2b, and 2c). The reappearance of hematoma in subdural spaces in subsequent scans following the evacuation of EDH prompts further surgical procedures that can cause extra surgical stress. Treatment strategies for acute SDH and EDH are based on the GCS score and volume of hematoma along with midline shift [13, 14]. EDH with a volume of 30 mL or more should be surgically evacuated [15]. The prognosis of EDH is extremely good if early surgical intervention is made. SDH with a thickness of greater than 10 mm or a midline shift of 5 mm should be operated by craniectomy or craniotomy with hematoma evacuation [14]. The prognosis of acute SDH usually depends on the preoperative status of the patient with the extent of primary brain injury. In our cases, delay in presentation, extent of primary brain injury, and radiological limitations in diagnosing both EDH and SDH, leading to further delay in complete evacuation of hematoma, were the main reasons for the poor prognosis of both patients. TBIs are an extremely common cause of mortality and morbidity in developing countries. A large number of cases of TBIs are being operated in these countries with limited resources. Sometimes, poor patients cannot afford multiple surgeries. Therefore, precise decision-making becomes vital to tackle these precarious situations. Through this article, the authors want to emphasize the fact that surgeons should keep in mind this type of radiological phenomenon, which in turn is useful in maximizing the limited resources of hospitals and minimizing the surgical burden of the patients.

Previously, a few isolated case reports have been published regarding this specific condition. Through this article, the authors are probably the first to report multiple cases in a single publication.

4. Conclusion

Coexisting EDH and SDH at the same location following TBI are extremely rare. Depending on the severity of brain injuries, early identification, and appropriate neurosurgical intervention are required. CT scans are the most common modalities to diagnose these lesions. Intraoperative dural pulsation and bulge determine the decision for durotomy. A large-sized hematoma needs surgical evacuation as early as possible, followed by dedicated neurosurgical care.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Written consent was obtained from the patient’s relatives to publish the history and corresponding radiological images.

Funding

This study did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Nityanand Pandey; Data collection: Vikrant Yadav; Data analysis and interpretation: Ravi Shankar Prasad; writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Debabrata Deb for his valuable opinion and support in drafting the manuscript.

References

3. Discussion

EDHs are fatal types of TBIs if left untreated. Crucial causes leading to the formation of EDH are middle meningeal vessel rupture, stripping of dural veins, fracture bleed, or sinus bleeding [7, 8]. EDH on CT scans appears as a crescentic or biconvex hyperdense lesion in the epidural space [9]. SDH is commonly caused by the rupture of veins that are deep into the dura mater. Acute SDH presents as a hyperdense collection in the subdural space that may be concavo-convex or irregular [5, 9]. In the first case, the cause of EDH was a fracture bleed with stripping of dural veins. In the second case, dural veins stripping with sinus bleed was the probable cause. In both cases, rupture of the deep venous system to the dura mater was the cause of SDH. These entities are easily identifiable on conventional CT scans when occur in different locations in the same patient. Sometimes, it is very difficult to differentiate both SDH from EDH when both occur in the same location, as evident in these two case reports. SDH may be obliterated radiologically, probably due to the large volume of EDH or the redistribution and dispersal of hematoma in subdural spaces [5, 10, 11, 12]. These situations can lead to the non-identification of hematoma in subdural spaces radiologically, which further leads to misjudgment of the appropriate surgical procedures and delay in adequate decompression of the brain. During the redistribution of hematoma, the mixing of cerebrospinal fluid gives SDH a mixed-density appearance [5]. In both reported cases, following the evacuation of EDH, the hematoma in subdural spaces appeared as mixed-density lesions on CT scans (Figures 1b, 2b, and 2c). The reappearance of hematoma in subdural spaces in subsequent scans following the evacuation of EDH prompts further surgical procedures that can cause extra surgical stress. Treatment strategies for acute SDH and EDH are based on the GCS score and volume of hematoma along with midline shift [13, 14]. EDH with a volume of 30 mL or more should be surgically evacuated [15]. The prognosis of EDH is extremely good if early surgical intervention is made. SDH with a thickness of greater than 10 mm or a midline shift of 5 mm should be operated by craniectomy or craniotomy with hematoma evacuation [14]. The prognosis of acute SDH usually depends on the preoperative status of the patient with the extent of primary brain injury. In our cases, delay in presentation, extent of primary brain injury, and radiological limitations in diagnosing both EDH and SDH, leading to further delay in complete evacuation of hematoma, were the main reasons for the poor prognosis of both patients. TBIs are an extremely common cause of mortality and morbidity in developing countries. A large number of cases of TBIs are being operated in these countries with limited resources. Sometimes, poor patients cannot afford multiple surgeries. Therefore, precise decision-making becomes vital to tackle these precarious situations. Through this article, the authors want to emphasize the fact that surgeons should keep in mind this type of radiological phenomenon, which in turn is useful in maximizing the limited resources of hospitals and minimizing the surgical burden of the patients.

Previously, a few isolated case reports have been published regarding this specific condition. Through this article, the authors are probably the first to report multiple cases in a single publication.

4. Conclusion

Coexisting EDH and SDH at the same location following TBI are extremely rare. Depending on the severity of brain injuries, early identification, and appropriate neurosurgical intervention are required. CT scans are the most common modalities to diagnose these lesions. Intraoperative dural pulsation and bulge determine the decision for durotomy. A large-sized hematoma needs surgical evacuation as early as possible, followed by dedicated neurosurgical care.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Written consent was obtained from the patient’s relatives to publish the history and corresponding radiological images.

Funding

This study did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Nityanand Pandey; Data collection: Vikrant Yadav; Data analysis and interpretation: Ravi Shankar Prasad; writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Debabrata Deb for his valuable opinion and support in drafting the manuscript.

References

- Haselsberger K, Pucher R, Auer LM. Prognosis after acute subdural or epidural haemorrhage. Acta Neurochirurgica. 1988; 90(3-4):111-6. [DOI:10.1007/BF01560563] [PMID]

- Gurer B, Kertmen H, Yilmaz ER, Dolgun H, Hasturk AE, Sekerci Z. The surgical outcome of traumatic extraaxial hematomas causing brain herniation. Turkish Neurosurgery. 2017; 27(1):37-52. [DOI:10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.14809-15.0] [PMID]

- Lavrador JP, Teixeira JC, Oliveira E, Simão D, Santos MM, Simas N. Acute subdural hematoma evacuation: Predictive factors of outcome. Asian Journal of Neurosurgery. 2018; 13(3):565-71. [DOI:10.4103/ajns.AJNS_51_16] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Atalay T, Ak H, Gülsen I, Karacabey S. Risk factors associated with mortality and survival of acute subdural hematoma: A retrospective study. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2019; 24:27. [DOI:10.4103/jrms.JRMS_14_16] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Basit J, Javed S, Shahzad F, Yaqoob E, Saeed S, Anand A. Coexistence of ipsilateral acute-on-chronic subdural hematoma and acute extradural hematoma: A case report. Clinical Case Reports. 2023; 11(7):e7684. [DOI:10.1002/ccr3.7684] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Gupta R, Mohindra S, Verma SR, Mohindra S, Verma SK. Traumatic ipsilateral acute extradural and subdural hematoma. Indian Journal of Neurotrauma. 2008; 05(02):113-4. [DOI:10.1016/S0973-0508(08)80011-1]

- Verma SK, Borkar SA, Singh PK, Tandon V, Gurjar HK, Sinha S, et al. Traumatic posterior fossa extradural hematoma: Experience at level I trauma center. Asian Journal of Neurosurgery. 2018; 13(2):227-32. [DOI:10.4103/1793-5482.228536] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Yadav V, Pandey N. Quartet of catastrophe: Bilateral epidural hematoma in both supratentorial and infratentorial compartments - A case report and a novel surgical technique to approach. Surgical Neurology International. 2023; 14:369. [DOI:10.25259/SNI_515_2023] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Heit JJ, Iv M, Wintermark M. Imaging of intracranial hemorrhage. Journal of Stroke. 2017; 19(1):11-27. [DOI:10.5853/jos.2016.00563] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kapsalaki EZ, Machinis TG, Robinson JS 3rd, Newman B, Grigorian AA, Fountas KN. Spontaneous resolution of acute cranial subdural hematomas. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2007; 109(3):287-91. [DOI:10.1016/j.clineuro.2006.11.005] [PMID]

- Vital RB, Hamamoto Filho PT, Oliveira VA, Romero FR, Zanini MA. Spontaneous resolution of traumatic acute subdural haematomas: A systematic review. Neurocirugia. 2016; 27(3):129-35. [DOI:10.1016/j.neucir.2015.05.003] [PMID]

- Kato N, Tsunoda T, Matsumura A, Yanaka K, Nose T. Rapid spontaneous resolution of acute subdural hematoma occurs by redistribution--Two case reports. Neurologia Medico-Chirurgica. 2001; 41(3):140-3. [DOI:10.2176/nmc.41.140] [PMID]

- Soon WC, Marcus H, Wilson M. Traumatic acute extradural haematoma - Indications for surgery revisited. British Journal of Neurosurgery. 2016; 30(2):233-4. [DOI:10.3109/02688697.2015.1119237] [PMID]

- Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, Gordon D, Hartl R, Newell DW, et al. Surgical management of acute subdural hematomas. Neurosurgery. 2006; 58(3 Suppl):S16-24. [DOI:10.1227/01.NEU.0000210364.29290.C9]

- Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, Gordon D, Hartl R, Newell DW, et al. Surgical management of acute epidural hematomas. Neurosurgery. 2006; 58(3 Suppl):S7-15. [DOI:10.1227/01.NEU.0000210363.91172.A8] [PMID]

Type of Study: Case report |

Subject:

Neurotrauma

Send email to the article author

| Rights and Permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

.jpg)