Mon, Feb 9, 2026

Volume 2, Issue 3 (12-2016)

Iran J Neurosurg 2016, 2(3): 22-25 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghalaenovi H, Azar M, Rahatlou H, Astaraki S. Chronic Subdural Hematoma after Lumboperitoneal Shunt Replacement: A Case Report From Iran. Iran J Neurosurg 2016; 2 (3) :22-25

URL: http://irjns.org/article-1-61-en.html

URL: http://irjns.org/article-1-61-en.html

1- Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery, Department of Neurological Surgery, Rasool Akram Complex, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Associate Professor of Neurosurgery, Department of Neurological Surgery, Rasool Akram Complex, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Resident of Neurosurgery, Department of Neurological Surgery, Rasool Akram Complex, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Neurosurgeon, Rasool Akram Complex, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Associate Professor of Neurosurgery, Department of Neurological Surgery, Rasool Akram Complex, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Resident of Neurosurgery, Department of Neurological Surgery, Rasool Akram Complex, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Neurosurgeon, Rasool Akram Complex, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full Text [PDF 1603 kb]

(3820 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (8604 Views)

Full Text: (2832 Views)

Background and Importance

Lumboperitoneal (LP) shunting is a method of diverting cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the subarachnoid space to the abdominal cavity. It has an overall incidence of 1.6/100,000 per annum [1], an unclear pathogenesis, although it has significantly higher incidence in obese females aged 20-44 at 19/100,000 [2]. The advantages of LP shunting include avoidance of brain penetration with the shunt catheter, access to a large CSF space in the thecal sac, and the potential (for good or ill) of a large amount of CSF drainage [3,4]. For the past 50 years, the mainstay of CSF shunting for idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), also known as pseudotumor cerebri (PTC) syndrome, has been LP shunt surgery [5,6]. Patients who require a LP shunt have a pathology that predisposes to the obstruction of CSF absorption or elevates the CSF pressure but must have communication of the spinal CSF with the cranial compartment. Specific indications include communicating hydrocephalus, normal pressure hydrocephalus, and IIH (PTC), though they are not limited to it [7-9]. Although the risk of intracranial complications after LP shunt insertion surgery is minimal, various complications have already been described, including shunt obstruction (14%), shunt infection (1%), radicular leg pain (5%), dyspnea, and disturbance of consciousness that necessitates conversion to a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt (1%) in patients who subsequently were noted to have Chiari malformations, shunt migration, and intracranial bleeding (2%) [3,10].

Case Presentation

Clinical Presentation and History

An obese 41-year-old woman was admitted to Rasool Akram Hospital presenting with headache, blurred vision, anxiety, and mental depression. She had been treated with acetazolamide for management of papilledema, which was unsuccessful, so she was referred to us. Her body mass index (BMI) was 38 kg/m2. Her medical history showed consumption of fluoxetine, Inderal, haloperidol, desipramine, and Artan, which were prescribed by her previous psychologist.

Diagnostic Measures

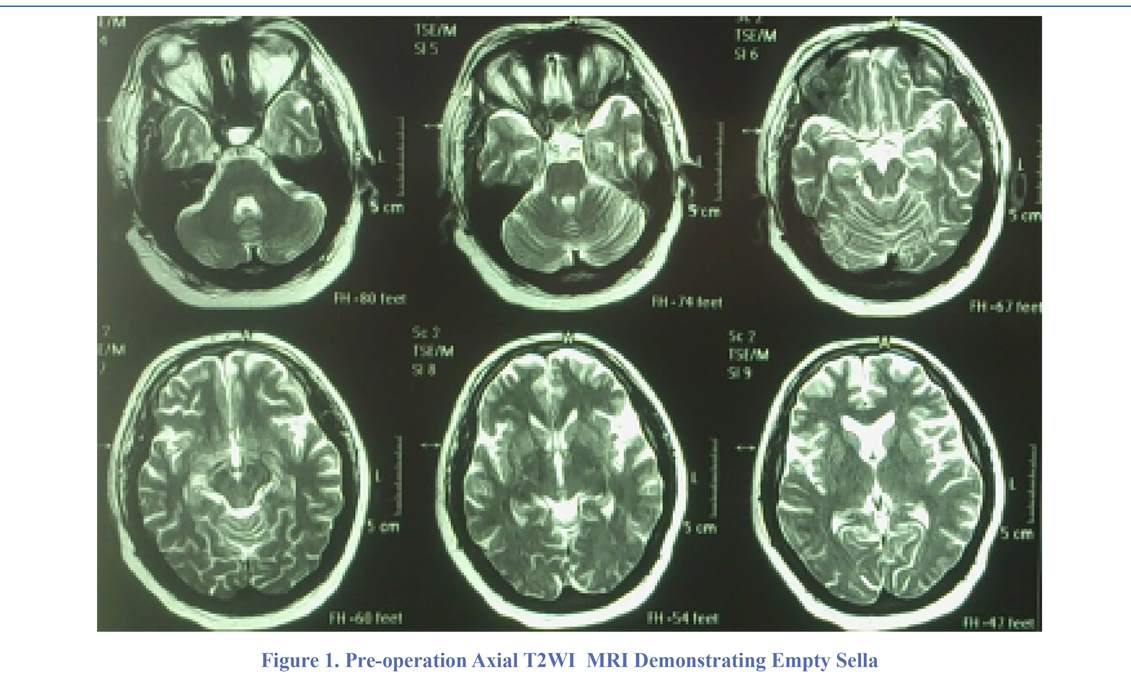

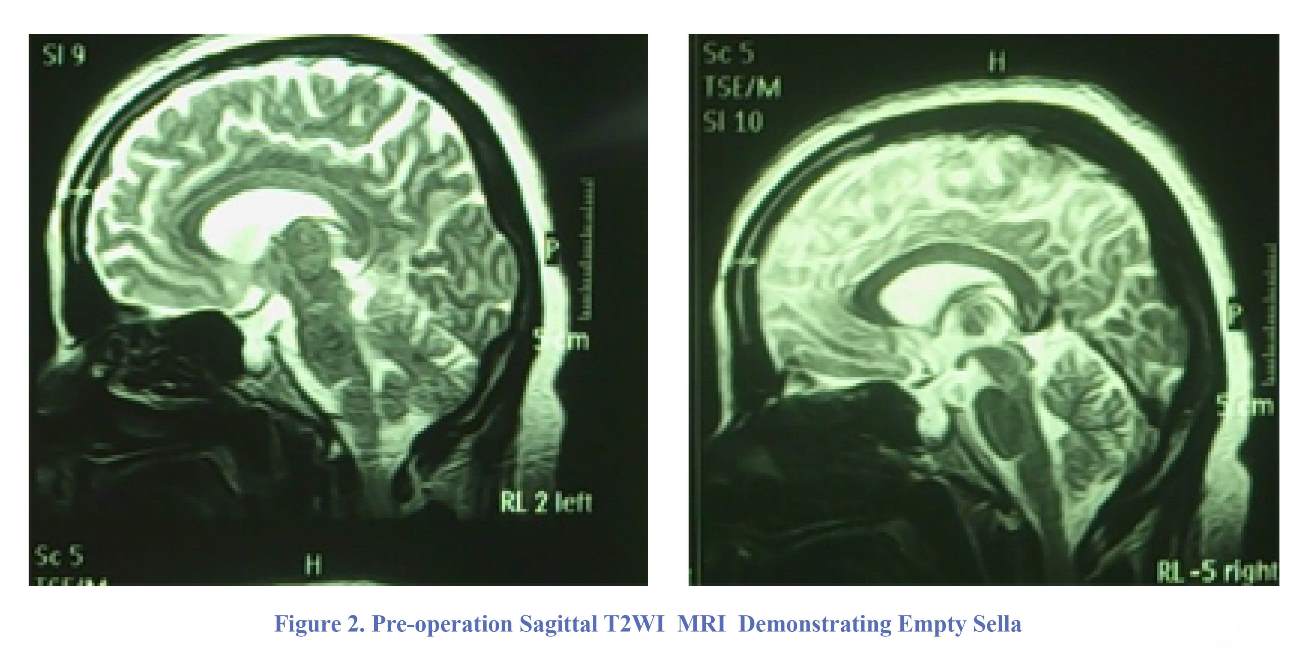

A neuro-ophthalmologist observed swelling in her bilateral optic disc. Visual field perimetry and visual acuity were in the normal range. Other general and neurological examinations did not reveal any abnormalities. The laboratory analysis of her blood showed hyperglycemia due to unmanaged diabetes mellitus (FBS: 180 mg/dl, normal range: 70-100 mg/dl) and hyperprolactinemia (Prolactin: 98 ng/mL, normal range: 2-29 ng/ml). A lumbar puncture was performed to evaluate her CSF. Although she consumed a 250-mg tablet of acetazolamide every eight hours, her lumbar puncture opening pressure was 33 cm H2O. Biochemistry and cytological analysis of CSF were within normal limits (Protein: 10 mg/dl, Sugar: 125 mg/dl, WBC: 0/hpf, RBC: 0/hpf). Her brain MRI before and after the administration of gadolinium had no abnormal findings except for the empty sella (Figures 1 & 2).

Lumboperitoneal (LP) shunting is a method of diverting cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the subarachnoid space to the abdominal cavity. It has an overall incidence of 1.6/100,000 per annum [1], an unclear pathogenesis, although it has significantly higher incidence in obese females aged 20-44 at 19/100,000 [2]. The advantages of LP shunting include avoidance of brain penetration with the shunt catheter, access to a large CSF space in the thecal sac, and the potential (for good or ill) of a large amount of CSF drainage [3,4]. For the past 50 years, the mainstay of CSF shunting for idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), also known as pseudotumor cerebri (PTC) syndrome, has been LP shunt surgery [5,6]. Patients who require a LP shunt have a pathology that predisposes to the obstruction of CSF absorption or elevates the CSF pressure but must have communication of the spinal CSF with the cranial compartment. Specific indications include communicating hydrocephalus, normal pressure hydrocephalus, and IIH (PTC), though they are not limited to it [7-9]. Although the risk of intracranial complications after LP shunt insertion surgery is minimal, various complications have already been described, including shunt obstruction (14%), shunt infection (1%), radicular leg pain (5%), dyspnea, and disturbance of consciousness that necessitates conversion to a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt (1%) in patients who subsequently were noted to have Chiari malformations, shunt migration, and intracranial bleeding (2%) [3,10].

Case Presentation

Clinical Presentation and History

An obese 41-year-old woman was admitted to Rasool Akram Hospital presenting with headache, blurred vision, anxiety, and mental depression. She had been treated with acetazolamide for management of papilledema, which was unsuccessful, so she was referred to us. Her body mass index (BMI) was 38 kg/m2. Her medical history showed consumption of fluoxetine, Inderal, haloperidol, desipramine, and Artan, which were prescribed by her previous psychologist.

Diagnostic Measures

A neuro-ophthalmologist observed swelling in her bilateral optic disc. Visual field perimetry and visual acuity were in the normal range. Other general and neurological examinations did not reveal any abnormalities. The laboratory analysis of her blood showed hyperglycemia due to unmanaged diabetes mellitus (FBS: 180 mg/dl, normal range: 70-100 mg/dl) and hyperprolactinemia (Prolactin: 98 ng/mL, normal range: 2-29 ng/ml). A lumbar puncture was performed to evaluate her CSF. Although she consumed a 250-mg tablet of acetazolamide every eight hours, her lumbar puncture opening pressure was 33 cm H2O. Biochemistry and cytological analysis of CSF were within normal limits (Protein: 10 mg/dl, Sugar: 125 mg/dl, WBC: 0/hpf, RBC: 0/hpf). Her brain MRI before and after the administration of gadolinium had no abnormal findings except for the empty sella (Figures 1 & 2).

Treatment

As a certain case of primary spontaneous PTC (intractable to medical therapy), the patient became a candidate for LP shunt surgery to channel the CSF from the lumbar thecal sac into the peritoneal cavity. During her hospitalization, she expressed no complaints except for low back pain (LBP) at the site of surgery, which was managed with regular analgesics, such as acetaminophen. The patient was discharged three days after the procedure, and she took a trip out of the country soon thereafter.

Post-operative Complications

The patient was referred to the hospital 20 days after the surgery and complained about nausea, vomiting, and headache. Because of the misdiagnosis of LP shunt-induced cerebellar tonsillar ptosis, she was conservatively treated with medications, such as promethazine and trifluoperazine. Her nausea and headache were exacerbated, and she was readmitted. Her computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain indicated left frontotemporoparietal subacute subdural

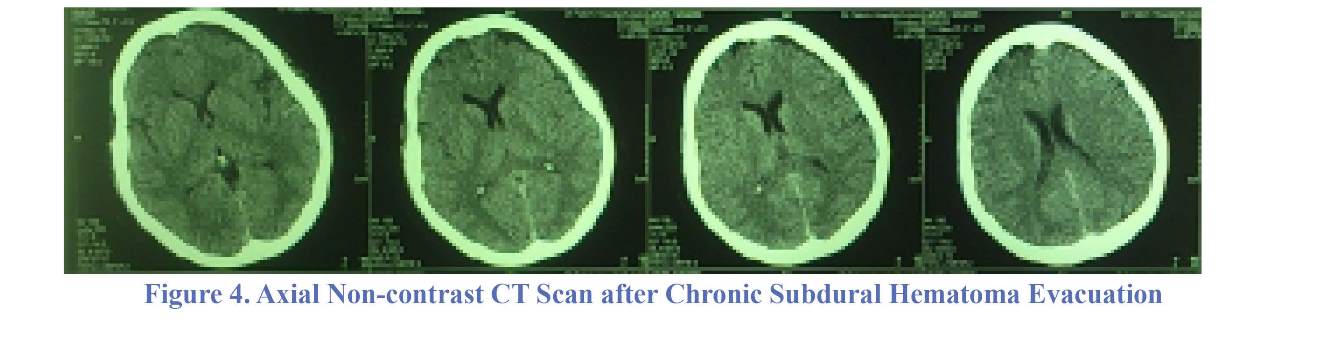

hematoma with subfalcine herniation (Figure 3). In her second surgery, the left parietal burr-hole was performed, and the subdural hematoma was evacuated. The post-operative period was uneventful, and her symptoms disappeared. Her delayed brain CT showed relief of hematoma and herniation (Figure 4).

Discussion

PTC, also called benign intracranial hypertension (BIH), is characterized by elevated intracranial pressure that is unrelated to hydrocephalus, tumor, brain edema, or any other structural entities associated with normal CSF analysis [11]. Usually, PTC presents with headache, and often there are changes in the vision of obese women of childbearing age [12]. Almost all patients with PTC have headaches, i.e., 90-94%. Their headaches are associated with a feeling of pressure and throbbing. The headaches are usually continual and occur with retro-ocular pain, and the patient may become nauseated [12,13]. Vision loss

As a certain case of primary spontaneous PTC (intractable to medical therapy), the patient became a candidate for LP shunt surgery to channel the CSF from the lumbar thecal sac into the peritoneal cavity. During her hospitalization, she expressed no complaints except for low back pain (LBP) at the site of surgery, which was managed with regular analgesics, such as acetaminophen. The patient was discharged three days after the procedure, and she took a trip out of the country soon thereafter.

Post-operative Complications

The patient was referred to the hospital 20 days after the surgery and complained about nausea, vomiting, and headache. Because of the misdiagnosis of LP shunt-induced cerebellar tonsillar ptosis, she was conservatively treated with medications, such as promethazine and trifluoperazine. Her nausea and headache were exacerbated, and she was readmitted. Her computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain indicated left frontotemporoparietal subacute subdural

hematoma with subfalcine herniation (Figure 3). In her second surgery, the left parietal burr-hole was performed, and the subdural hematoma was evacuated. The post-operative period was uneventful, and her symptoms disappeared. Her delayed brain CT showed relief of hematoma and herniation (Figure 4).

Discussion

PTC, also called benign intracranial hypertension (BIH), is characterized by elevated intracranial pressure that is unrelated to hydrocephalus, tumor, brain edema, or any other structural entities associated with normal CSF analysis [11]. Usually, PTC presents with headache, and often there are changes in the vision of obese women of childbearing age [12]. Almost all patients with PTC have headaches, i.e., 90-94%. Their headaches are associated with a feeling of pressure and throbbing. The headaches are usually continual and occur with retro-ocular pain, and the patient may become nauseated [12,13]. Vision loss

is the most-feared result of PTC, but it is usually temporary.

Approximately 68-85% of such patients experience vision loss [12-15]. There are usually impairments in the visual field, the most common of which is tunnel vision [12]. The vision changes are usually explained as transient ischemia of the optic nerve due to pressure [15]. Photopsia (54%) and eye pain (44%) are other common symptoms [15]. More severe symptoms occur infrequently, but diplopia (38%) and vision loss (30%) occur in a significant number of patients [15].

There is a wide variety of treatment options for BIH. Initially, it may be treated with medications, such as acetazolamide. Subsequently, surgical and non-surgical treatments may be necessary. More aggressive measures for preventing sequelae of PTC are typically used for two groups of patients, i.e., those who continue to experience vision loss despite conservative management and those who initially have rapid loss of vision. LP shunt surgery is a method in which the elevated CSF pressure is referred to the peritoneal cavity, but it entails serious risk of complications that can range from obstruction of the shunt, shunt-related meningitis, abdominal infections, tonsillar herniation, and even death [13]. Shunts fail in about 50% of patients, and approximately 10% of patients have worsening vision after the shunt surgery. Thus, frequent neurologic follow-up is required after shunts are placed [15,16].

Many ophthalmologists advocate decompression as an alternative surgical approach, because it has fewer complications and better outcomes [13,17]. The LP shunt is inserted into the subarachnoid cavity between two of the vertebrae in the lumbar region of the spine. This cavity is also referred to as the subarachnoid space. The cavity is a spongy,

tissue-filled area that surrounds the brain and spinal cord, and it contains the CSF. The shunt is placed under the skin, and it continues around the oblique muscles on one side of the body. The shunt ends at the peritoneal cavity in the abdominal area. After the LP shunt is in place, it is used to drain excess CSF from the brain via the subarachnoid cavity. The fluid is transported to the peritoneal cavity, where it is absorbed and eliminated in the urine [18].

In the presented case, there was an obese 41-year-old woman who complained of severe headache, anxiety, and blurred vision. In her physical examination, bilateral papilledema was detected. The only abnormal finding in the patient’s imaging was empty sella, and no subarachnoid space widening was observed. The diagnosis was PTC, and a LP shunt was placed. The patient was discharged three days after the procedure. She was referred to hospital 20 days later and complained of headache, nausea, and vomiting. The patient was treated conservatively with medications, such as promethazine and trifluoperazine. LP shunt-induced cerebellar tonsillar ptosis was suspected, but after the exacerbation of her symptoms, a CT of the brain was performed, and it indicated the presence of a left frontotemporoparietal, subacute, subdural hematoma with subfalcine herniation. The subdural hematoma was evacuated in the second surgery, and her symptoms disappeared thereafter.

Conclusion

No history of head trauma of any kind was reported in our patient. Contrary to hydrocephalic patients, the literature did not provide any previous report of subacute

or chronic subdural hematoma subsequent to placement of LP shunt in patients with BIH. Persistent symptoms, such as headache, nausea, and vomiting, after placement of a LP shunt should not be taken for granted. CT imaging is essential to rule out subdural hematoma.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Department of Neurosurgery, Faculty of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences and the Research Deputy for the financial support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution

Conception and Design: All authors. Data Collection: All authors. Drafting the Article: All authors. Critical Revising the Article: All authors. Reviewing Submitted Version of Manuscript: All authors. Approving the Final Version of the Manuscript: All authors.

References

1. McGeeney BE, Friedman DI. Pseudotumor cerebri pathophysiology. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2014;54(3):445-58.

2. Durcan PJ, Corbett JJ, Wall M. The incidence of pseudotumor cerebri: population studies in Iowa and Louisiana. Archives of Neurology. 1988;45(8):875-7.

3. Aoki N. Lumboperitoneal shunt: clinical applications, complications, and comparison with ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Neurosurgery. 1990;26(6):998-1004.

4. Uretsky S. Surgical interventions for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2009;20(6):451-5.

5. Mcgirt MJ, Woodworth G, Thomas G, Miller N, Williams M, Rigamonti D. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt placement for pseudotumor cerebri-associated intractable headache: predictors of treatment response and an analysis of long-term outcomes. Journal of neurosurgery. 2004;101(4):627-32.

6. Stein SC, Guo W. Have we made progress in preventing shunt failure? A critical analysis. 2008.

7. Garton HJ. Cerebrospinal fluid diversion procedures. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology. 2004;24(2):146-55.

8. Brazis P. Clinical review: the surgical treatment of idiopathic pseudotumour cerebri (idiopathic intracranial hypertension). Cephalalgia. 2008;28(12):1361-73.

9. Chang C-C, Kuwana N, Ito S. Management of patients with normal-pressure hydrocephalus by using lumboperitoneal shunt system with the Codman Hakim programmable valve. Neurosurgical focus. 1999;7(4):E9.

10. Kamiryo T, Hamada J-i, Fuwa I, Ushio Y. Acute Subdural Hematoma After Lumboperitoneal Shunt Placement in Patients With Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus-Four Case Reports. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2003;43(4):197-200.

11. Suri A, Pandey P, Mehta V. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and intracereebral hematoma following lumboperitoneal shunt for pseudotumor cerebri: a rare complication. Neurology India. 2002;50(4):508.

12. Levin LA. Neuro-ophthalmology: the practical guide: Thieme; 2005.

13. Lueck CJ, McIlwaine GG. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Practical neurology. 2002;2(5):262-71.

14. Rowe FJ, Sarkies NJ. Assessment of visual function in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a prospective study. Eye. 1998;12(1):111-8.

15. Wall M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurologic clinics. 2010;28(3):593-617.

16. Mathews MK, Sergott RC, Savino PJ. Pseudotumor cerebri. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2003;14(6):364-70.

17. Yazici Z, Yazici B, Tuncel E. Findings of magnetic resonance imaging after optic nerve sheath decompression in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007;144(3):429-35. e1.

18. Excellence NIfHaC. Interventional Procedure Guidance 68 (IPG068): Lumbar subcutaneous shunt 2004. Available from: Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg68.

Comments

The authors of this case report speak about a rewarding experience. This complication is not rare and must be expected when persistent headache and vomiting appear after lumboperitoneal shunt replacement. This is a good case is as school case: little diameter of drain or low drainage pressure is not sufficient conditions to prevent complications in patient who had cranial hypertension even case of Pseudotumor cerebri.

Holden Fatigba, MD, Professor of Neurosurgery, Teaching Hospital and Medicine School of Parakou, Benin (West Africa)

Dear editor,

Ghalaenovi and colleagues wrote: "The literature did not provide any previous report of subacute or chronic subdural hematoma subsequent to placement of LP shunt in patients with BIH" [1].

Chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) is a well-known complication following placement of lunboperitoneal (LP) shunt in patients with benign intracranial hypertension (BIH) [2,3].

Twenty-seven years ago, Aoki showed there is 1% CSDH and 2% acute SDH following LP insertion among 207 cases of BIH [2].

Matsubara and colleagues showed that the mechanism of CSDH in their patient was the lumbar tip of the shunt which pulled out dura and increased the epidural space. Then, CSF came out of the shunt side hole and accumulated in the epidural space [3].

Vafa Rahimi-Movaghar, MD, Professor of Neurosurgery, Research Vice President of Sina Trauma and Surgery Research Center

Department of Neurosurgery, Shariati Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

AOSpine Research Officer of Middle East, Director of National Spinal Cord Injury in Iran, Research Center for Neural Repair, University of Tehran

Approximately 68-85% of such patients experience vision loss [12-15]. There are usually impairments in the visual field, the most common of which is tunnel vision [12]. The vision changes are usually explained as transient ischemia of the optic nerve due to pressure [15]. Photopsia (54%) and eye pain (44%) are other common symptoms [15]. More severe symptoms occur infrequently, but diplopia (38%) and vision loss (30%) occur in a significant number of patients [15].

There is a wide variety of treatment options for BIH. Initially, it may be treated with medications, such as acetazolamide. Subsequently, surgical and non-surgical treatments may be necessary. More aggressive measures for preventing sequelae of PTC are typically used for two groups of patients, i.e., those who continue to experience vision loss despite conservative management and those who initially have rapid loss of vision. LP shunt surgery is a method in which the elevated CSF pressure is referred to the peritoneal cavity, but it entails serious risk of complications that can range from obstruction of the shunt, shunt-related meningitis, abdominal infections, tonsillar herniation, and even death [13]. Shunts fail in about 50% of patients, and approximately 10% of patients have worsening vision after the shunt surgery. Thus, frequent neurologic follow-up is required after shunts are placed [15,16].

Many ophthalmologists advocate decompression as an alternative surgical approach, because it has fewer complications and better outcomes [13,17]. The LP shunt is inserted into the subarachnoid cavity between two of the vertebrae in the lumbar region of the spine. This cavity is also referred to as the subarachnoid space. The cavity is a spongy,

tissue-filled area that surrounds the brain and spinal cord, and it contains the CSF. The shunt is placed under the skin, and it continues around the oblique muscles on one side of the body. The shunt ends at the peritoneal cavity in the abdominal area. After the LP shunt is in place, it is used to drain excess CSF from the brain via the subarachnoid cavity. The fluid is transported to the peritoneal cavity, where it is absorbed and eliminated in the urine [18].

In the presented case, there was an obese 41-year-old woman who complained of severe headache, anxiety, and blurred vision. In her physical examination, bilateral papilledema was detected. The only abnormal finding in the patient’s imaging was empty sella, and no subarachnoid space widening was observed. The diagnosis was PTC, and a LP shunt was placed. The patient was discharged three days after the procedure. She was referred to hospital 20 days later and complained of headache, nausea, and vomiting. The patient was treated conservatively with medications, such as promethazine and trifluoperazine. LP shunt-induced cerebellar tonsillar ptosis was suspected, but after the exacerbation of her symptoms, a CT of the brain was performed, and it indicated the presence of a left frontotemporoparietal, subacute, subdural hematoma with subfalcine herniation. The subdural hematoma was evacuated in the second surgery, and her symptoms disappeared thereafter.

Conclusion

No history of head trauma of any kind was reported in our patient. Contrary to hydrocephalic patients, the literature did not provide any previous report of subacute

or chronic subdural hematoma subsequent to placement of LP shunt in patients with BIH. Persistent symptoms, such as headache, nausea, and vomiting, after placement of a LP shunt should not be taken for granted. CT imaging is essential to rule out subdural hematoma.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Department of Neurosurgery, Faculty of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences and the Research Deputy for the financial support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution

Conception and Design: All authors. Data Collection: All authors. Drafting the Article: All authors. Critical Revising the Article: All authors. Reviewing Submitted Version of Manuscript: All authors. Approving the Final Version of the Manuscript: All authors.

References

1. McGeeney BE, Friedman DI. Pseudotumor cerebri pathophysiology. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2014;54(3):445-58.

2. Durcan PJ, Corbett JJ, Wall M. The incidence of pseudotumor cerebri: population studies in Iowa and Louisiana. Archives of Neurology. 1988;45(8):875-7.

3. Aoki N. Lumboperitoneal shunt: clinical applications, complications, and comparison with ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Neurosurgery. 1990;26(6):998-1004.

4. Uretsky S. Surgical interventions for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2009;20(6):451-5.

5. Mcgirt MJ, Woodworth G, Thomas G, Miller N, Williams M, Rigamonti D. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt placement for pseudotumor cerebri-associated intractable headache: predictors of treatment response and an analysis of long-term outcomes. Journal of neurosurgery. 2004;101(4):627-32.

6. Stein SC, Guo W. Have we made progress in preventing shunt failure? A critical analysis. 2008.

7. Garton HJ. Cerebrospinal fluid diversion procedures. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology. 2004;24(2):146-55.

8. Brazis P. Clinical review: the surgical treatment of idiopathic pseudotumour cerebri (idiopathic intracranial hypertension). Cephalalgia. 2008;28(12):1361-73.

9. Chang C-C, Kuwana N, Ito S. Management of patients with normal-pressure hydrocephalus by using lumboperitoneal shunt system with the Codman Hakim programmable valve. Neurosurgical focus. 1999;7(4):E9.

10. Kamiryo T, Hamada J-i, Fuwa I, Ushio Y. Acute Subdural Hematoma After Lumboperitoneal Shunt Placement in Patients With Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus-Four Case Reports. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2003;43(4):197-200.

11. Suri A, Pandey P, Mehta V. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and intracereebral hematoma following lumboperitoneal shunt for pseudotumor cerebri: a rare complication. Neurology India. 2002;50(4):508.

12. Levin LA. Neuro-ophthalmology: the practical guide: Thieme; 2005.

13. Lueck CJ, McIlwaine GG. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Practical neurology. 2002;2(5):262-71.

14. Rowe FJ, Sarkies NJ. Assessment of visual function in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a prospective study. Eye. 1998;12(1):111-8.

15. Wall M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurologic clinics. 2010;28(3):593-617.

16. Mathews MK, Sergott RC, Savino PJ. Pseudotumor cerebri. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2003;14(6):364-70.

17. Yazici Z, Yazici B, Tuncel E. Findings of magnetic resonance imaging after optic nerve sheath decompression in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007;144(3):429-35. e1.

18. Excellence NIfHaC. Interventional Procedure Guidance 68 (IPG068): Lumbar subcutaneous shunt 2004. Available from: Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg68.

Comments

The authors of this case report speak about a rewarding experience. This complication is not rare and must be expected when persistent headache and vomiting appear after lumboperitoneal shunt replacement. This is a good case is as school case: little diameter of drain or low drainage pressure is not sufficient conditions to prevent complications in patient who had cranial hypertension even case of Pseudotumor cerebri.

Holden Fatigba, MD, Professor of Neurosurgery, Teaching Hospital and Medicine School of Parakou, Benin (West Africa)

Dear editor,

Ghalaenovi and colleagues wrote: "The literature did not provide any previous report of subacute or chronic subdural hematoma subsequent to placement of LP shunt in patients with BIH" [1].

Chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) is a well-known complication following placement of lunboperitoneal (LP) shunt in patients with benign intracranial hypertension (BIH) [2,3].

Twenty-seven years ago, Aoki showed there is 1% CSDH and 2% acute SDH following LP insertion among 207 cases of BIH [2].

Matsubara and colleagues showed that the mechanism of CSDH in their patient was the lumbar tip of the shunt which pulled out dura and increased the epidural space. Then, CSF came out of the shunt side hole and accumulated in the epidural space [3].

Vafa Rahimi-Movaghar, MD, Professor of Neurosurgery, Research Vice President of Sina Trauma and Surgery Research Center

Department of Neurosurgery, Shariati Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

AOSpine Research Officer of Middle East, Director of National Spinal Cord Injury in Iran, Research Center for Neural Repair, University of Tehran

Type of Study: Case report |

Subject:

Gamma Knife Radiosurgery

References

1. McGeeney BE, Friedman DI. Pseudotumor cerebri pathophysiology. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2014;54(3):445-58. [DOI:10.1111/head.12291] [PMID]

2. Durcan PJ, Corbett JJ, Wall M. The incidence of pseudotumor cerebri: population studies in Iowa and Louisiana. Archives of Neurology. 1988;45(8):875-7. [DOI:10.1001/archneur.1988.00520320065016] [PMID]

3. Aoki N. Lumboperitoneal shunt: clinical applications, complications, and comparison with ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Neurosurgery. 1990;26(6):998-1004.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00006123-199006000-00013 [DOI:10.1227/00006123-199006000-00013] [PMID]

4. Uretsky S. Surgical interventions for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2009;20(6):451-5. [DOI:10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283313c1c] [PMID]

5. Mcgirt MJ, Woodworth G, Thomas G, Miller N, Williams M, Rigamonti D. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt placement for pseudotumor cerebri-associated intractable headache: predictors of treatment response and an analysis of long-term outcomes. Journal of neurosurgery. 2004;101(4):627-32. [DOI:10.3171/jns.2004.101.4.0627] [PMID]

6. Stein SC, Guo W. Have we made progress in preventing shunt failure? A critical analysis. 2008.

7. Garton HJ. Cerebrospinal fluid diversion procedures. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology. 2004;24(2):146-55. [DOI:10.1097/00041327-200406000-00010] [PMID]

8. Brazis P. Clinical review: the surgical treatment of idiopathic pseudotumour cerebri (idiopathic intracranial hypertension). Cephalalgia. 2008;28(12):1361-73. [DOI:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01778.x] [PMID]

9. Chang C-C, Kuwana N, Ito S. Management of patients with normal-pressure hydrocephalus by using lumboperitoneal shunt system with the Codman Hakim programmable valve. Neurosurgical focus. 1999;7(4):E9. [DOI:10.3171/foc.1999.7.4.10]

10. Kamiryo T, Hamada J-i, Fuwa I, Ushio Y. Acute Subdural Hematoma After Lumboperitoneal Shunt Placement in Patients With Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus-Four Case Reports. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2003;43(4):197-200. [DOI:10.2176/nmc.43.197] [PMID]

11. Suri A, Pandey P, Mehta V. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and intracereebral hematoma following lumboperitoneal shunt for pseudotumor cerebri: a rare complication. Neurology India. 2002;50(4):508. [PMID]

12. Levin LA. Neuro-ophthalmology: the practical guide: Thieme; 2005.

13. Lueck CJ, McIlwaine GG. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Practical neurology. 2002;2(5):262-71. [DOI:10.1046/j.1474-7766.2002.00084.x]

14. Rowe FJ, Sarkies NJ. Assessment of visual function in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a prospective study. Eye. 1998;12(1):111-8. [DOI:10.1038/eye.1998.18] [PMID]

15. Wall M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurologic clinics. 2010;28(3):593-617. [DOI:10.1016/j.ncl.2010.03.003] [PMID] [PMCID]

16. Mathews MK, Sergott RC, Savino PJ. Pseudotumor cerebri. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2003;14(6):364-70. [DOI:10.1097/00055735-200312000-00008] [PMID]

17. Yazici Z, Yazici B, Tuncel E. Findings of magnetic resonance imaging after optic nerve sheath decompression in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007;144(3):429-35. e1.

18. Excellence NIfHaC. Interventional Procedure Guidance 68 (IPG068): Lumbar subcutaneous shunt 2004. Available from: Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg68.

| Rights and Permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |