Sat, Jan 31, 2026

Volume 11 - Continuous Publishing

Iran J Neurosurg 2025, 11 - Continuous Publishing: 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: 23/452

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rajkumar P, Subramanian T, Duraisamy J, Shankar Komarraju A. Retrospective Analysis of two different Cranioplasty Methods : A Single Institution Experience. Iran J Neurosurg 2025; 11 : 20

URL: http://irjns.org/article-1-467-en.html

URL: http://irjns.org/article-1-467-en.html

1- Department of Neurosurgery, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Coimbatore, India.

2- Department of Neurosurgery, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Coimbatore, India. ,jayaprakashduraisamy@yahoo.com

2- Department of Neurosurgery, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Coimbatore, India. ,

Full Text [PDF 975 kb]

(24 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (86 Views)

Full Text: (9 Views)

1. Background and Importance

The occurrence of traumatic brain injury following road traffic accidents, assault, fall from height, and stroke (both hemorrhagic and ischemic) has become intensely common over the last two decades.

Monro-Kellie doctrine states that “the sum of all volumes of the brain, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and intracranial blood is constant”[1]. Following brain injury, this equilibrium is disrupted, resulting in increased intracranial pressure (ICP), which causes a decrease in cerebral blood flow due to a fall in cerebral perfusion pressure. To manage this damage, decompressive craniectomy was considered as an emergency life-saving procedure. The purpose is to reduce the raised ICP and to minimize the chances of brain ischemia [1, 2].

Decompressive craniectomy is a life-saving neurosurgical procedure done to relieve increased intracranial tension refractory to medical management [2]. This condition involves the removal of a wide portion of the skull bone to evacuate the brain hemorrhage (epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, or intracerebral hemorrhage)and to accommodate the brain swelling. The standard decompressive craniectomy includes the removal of a 15x12 cm bone flap in the fronto-temporo-parietal region (FTP) to reduce the mortality and to improve the neurological condition.

Indications and contraindications for cranioplasty

A few months after decompressive craniectomy, once the brain swelling settles, the new gradient between the atmospheric and ICP can result in neurological deterioration [2, 3].

In 1939, Grant and Norcross observed that after a few months of craniectomy, many patients developed severe headaches, altered cognitive behaviors, giddiness, and pain at the craniectomy site. It was later defined as Trephined syndrome [2].

The three main components of this condition include the occurrence of neurological deficits weeks to months after decompressive craniectomy, newly arising neurological deficits not associated with primary pathology, and clinical resolution after cranioplasty [2].

The neurological deficit that occurs a few months after craniectomy is called sunken flap syndrome, and if it restores with cranioplasty, it is taken as trephined syndrome. in clinical practice, however, the terms “sunken flap syndrome” and “trephined syndrome” are often used interchangeably.

Cranioplasty stabilizes the brain-atmospheric pressure difference and restores the physiology of the closed cavity, allowing the brain parenchyma to re-expand. The disturbance in CSF hydrodynamics and cerebral perfusion is well described in the chronic phase of decompressive craniectomy, and it is improved following cranioplasty [3].

Cranioplasty is done to reconstruct the skull 3-4 months after a decompressive craniectomy. This time gap is given for the brain to expand extracranially as a consequence of raised intracranial tension. This procedure holds a multitude of benefits. Besides protecting the brain parenchyma and cosmesis, it restores the physiology of the closed cavity, improves CSF dynamics, which is disrupted following craniectomy, as the atmospheric pressure exerts an influence on the brain and CSF [3]. This procedure also reduces the formation of pseudo-meningocele.

Meningitis, encephalitis, wound infection and sepsis, osteomyelitis, unmanaged post-traumatic hydrocephalus with brain herniation through the cranial cavity area few contraindications for cranioplasty.

Materials used

An ideal cranioplasty material should be inert, malleable, lightweight, readily incorporated with the existing skull bone, but not interfere with radiological imaging. Various materials have been used for cranial implants throughout history. Meekeren described the first documented evidence of cranioplasty using bone in 1668, when he repaired the skull of a Russian nobleman using the skull of a dead dog [4].

Moving forward to the 20th century showed the advent of homologous and autologous bone grafts. Autologous boneis the cheapest physiologic alternative to synthetic materials. Being the body’s tissue, it is viable, ie, has the potential to grow and does not fracture or get displaced easily [1, 5]. The main risk in using autologous bone includes infection, resorption, and flap collapse [5]. Another challenge in using autologous bone is the preservation of the graft between the time of removal and implantation. A common method of conservation is storing the autologous bone in the subcutaneous space of the abdomen and thigh. Cryopreservation at -70 °C has also been proven effective [6, 7].

Aluminum was the first metal to be used for making bone grafts, but it had high resorption rates and was known to reduce seizure threshold in patients [4, 8].

Silver and Gold were also used initially. However, they were expensive and their use was eventually discontinued [4]. Tantalum was an inert metal briefly used for cranioplasty during the early 1940s. [4, 8, 9]. Titanium was then used in place of Tantalum due to its low thermal conductivity and low radio-opacity.

Next, hydroxyapatite was used because it closely resembles human bone chemically. However, difficulty in contouring and the brittleness of hydroxyapatite rendered it practically obsolete [4, 8].

The interest then shifted to non-metals for grafting after seeing the success with dental implants. Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), discovered in 1940, is the most widely used prosthesis today. It is available in a powdered form, which, when mixed with benzoyl peroxide, produces an exothermic reaction followed by cooling. This process shapes the material to resemble the original bone. Despite giving excellent cosmetic results and making the radiological imaging process easier, PMMA did not integrate well with the surrounding tissue. It was prone to develop a fibrous coat over its surface, predisposing it to infections [1, 4, 10]. The intra-operative time was also longer due to the molding and cooling process.

One of the reasons why PSIs are so necessary is the immense diversity in the properties of each cranial bone, including its shape, thickness, andporosity. Each part of the same cranial bone also had different tensile strengths. Therefore, the type and design of the implant changes based on the anatomical location of the cranial defect. Initially, manufacturing craniofacial implants required a long, drawn-out process involving molding, casting, and extrusion, which offered fair accuracy but minimal cost benefits [11]. Later, 3D printing technologies developed, enabling neurosurgeons to manufacture PSIs using CT images to set the dimensions of the implant. This capability gave a lesser scope for error, shorter intra-operative time, and higher patient satisfaction [12].

Procedure

The procedure includes incision of the previous craniectomy scar, creation of a plane between dura mater and scalp, raising the scalp flap, raising the temporalis muscle flap, defining the bone defect all around, choosing the material for cranioplasty, fixing the cranioplasty material to the skull bone defect with titanium screws, placing a subgaleal drain, and suturing. Administering intraoperative anesthesia just before skin incision is widely adopted, but the frequency and duration of post-operative antibiotics are not clear.

2. Case Presentation

This research was a retrospective analysis study of the patients admitted to the neurosurgery ICU at PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Coimbatore, India, from January 2014 to January 2023.

Patients admitted with a previous history of FTP, decompressive craniectomy for traumatic brain injury (epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, or intracerebral hemorrhage), and for stroke (ischemic and hemorrhagic), with Glasgow coma scale (GCS) >13, skull defect >5 cm, and without surgical site infection were included in the study.

Patients who have undergone decompressive craniectomy for subdural empyema, brain abscess, Malignancies, GCS<13, and those who have surgical site infection were excluded from the study. Pediatric patients (<10 years) with decompressive craniectomy defects were also excluded from the study.

Computed tomography (CT) scans of the patient’s head post-decompressive craniectomy is done in our hospital; the necessary data is stored in digital imaging and communication in medicine (DICOM) format. These data are processed to create a virtual 3D patient model, after which titanium mesh is manufactured accordingly. Depending on the anatomical location of the cranial defect, the thickness of the mesh was between 0.3 mm and 0.6 mm. The mesh was sterilized under an autoclave before surgery.

3. Discussion

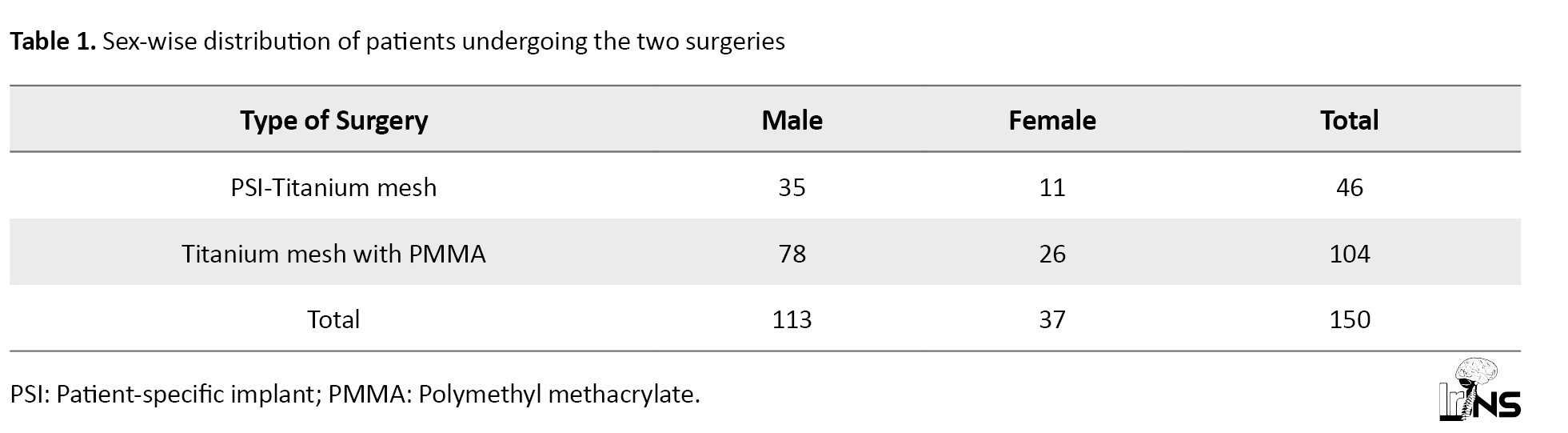

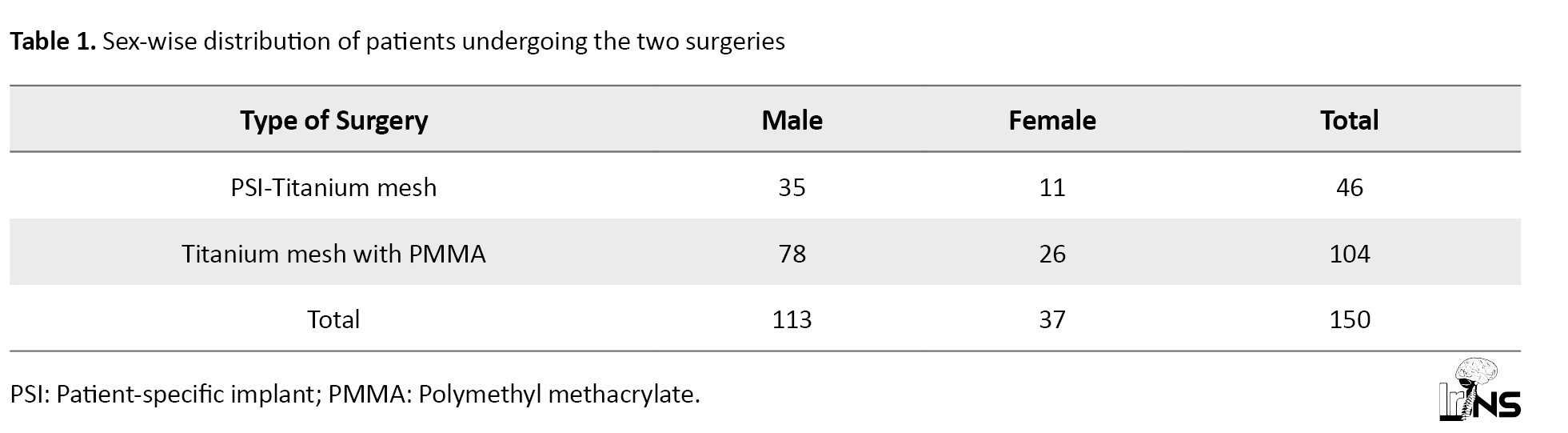

Of 150 patients admitted to the Neurosurgery ICU with decompressive craniectomy defects, 104 patients (69.3%) underwent cranioplasty with titanium mesh - PMMA implant, and 46 patients (30.7%) underwent cranioplasty with patient-specific titanium plate implant. Also, 75% of the patients were male, and 25% were female (Table 1).

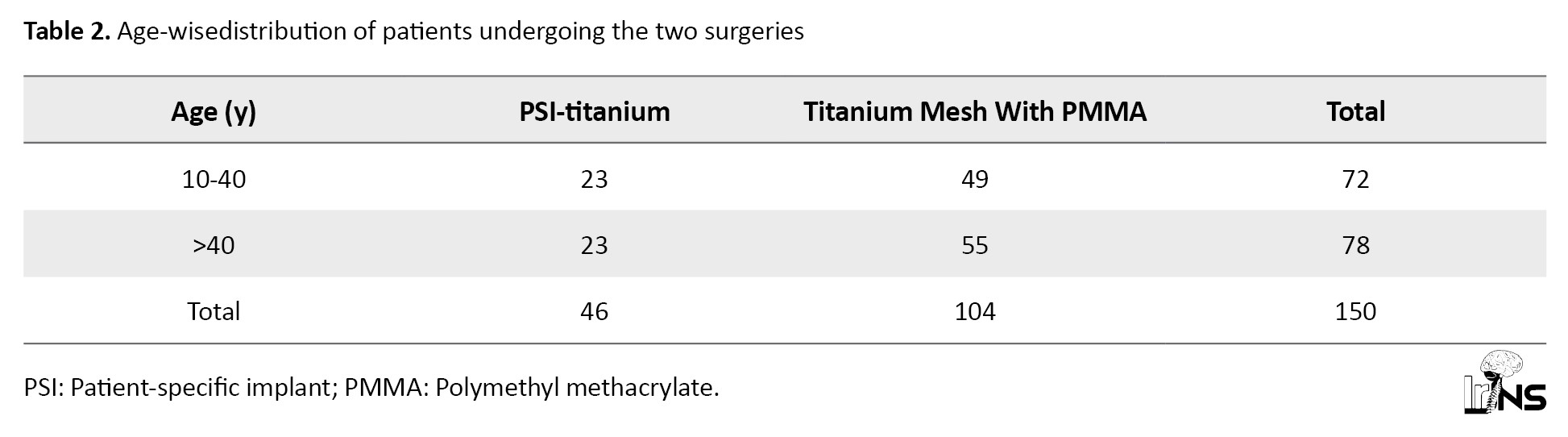

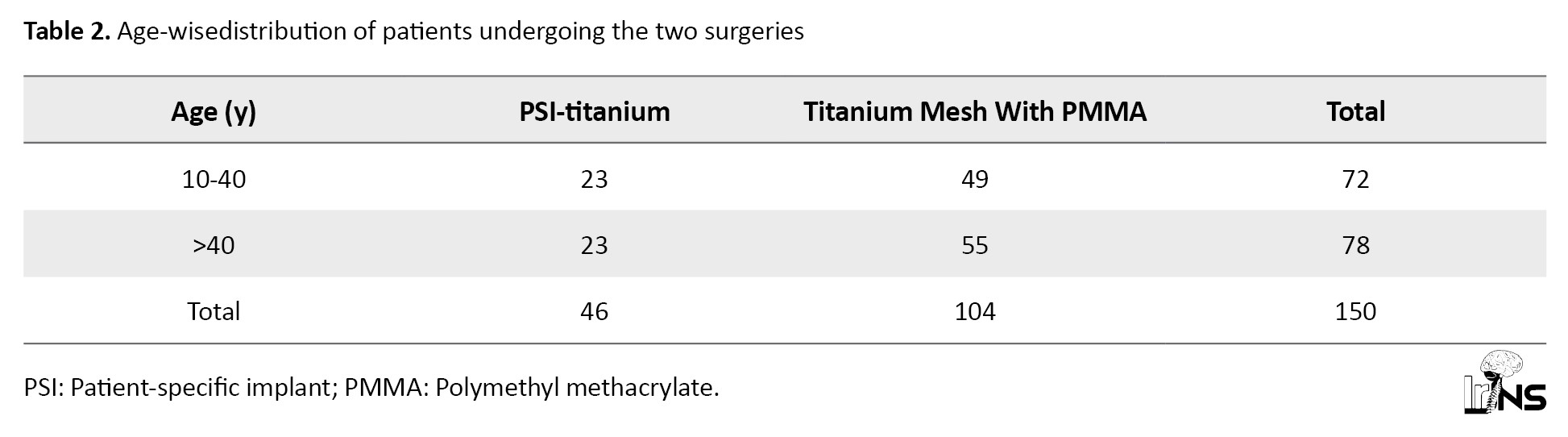

About 48% of patients were between 10 and 40 years old, and 52% aged above 40 years (Table 2).

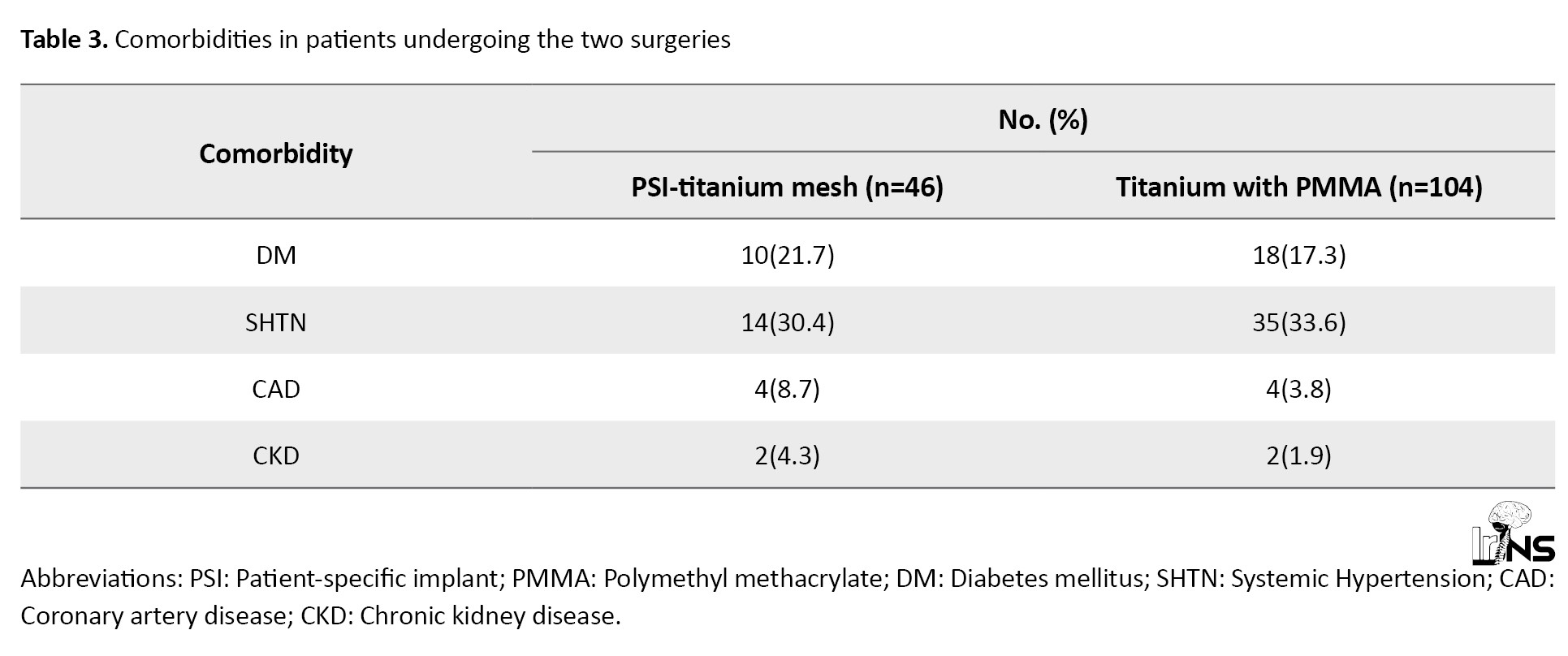

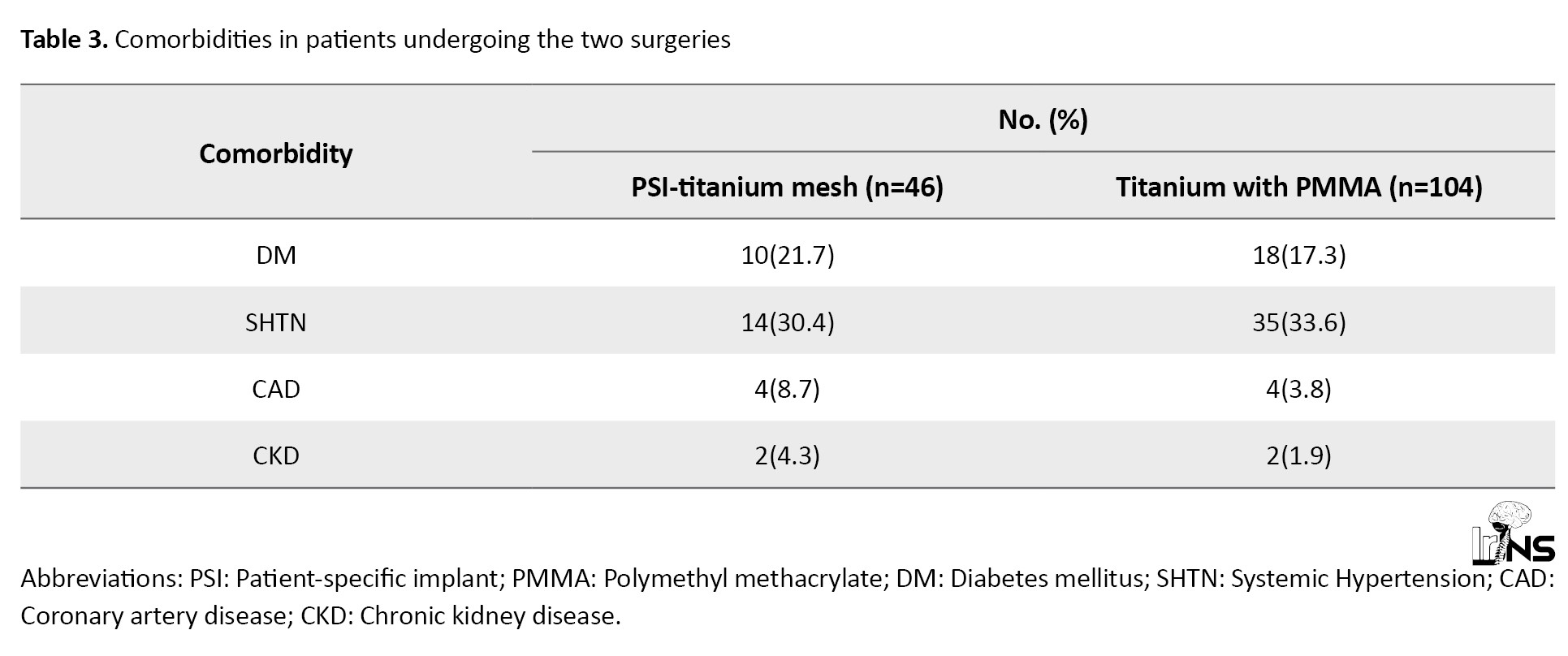

Table 3 highlights the various comorbidities of patients undergoing the study.

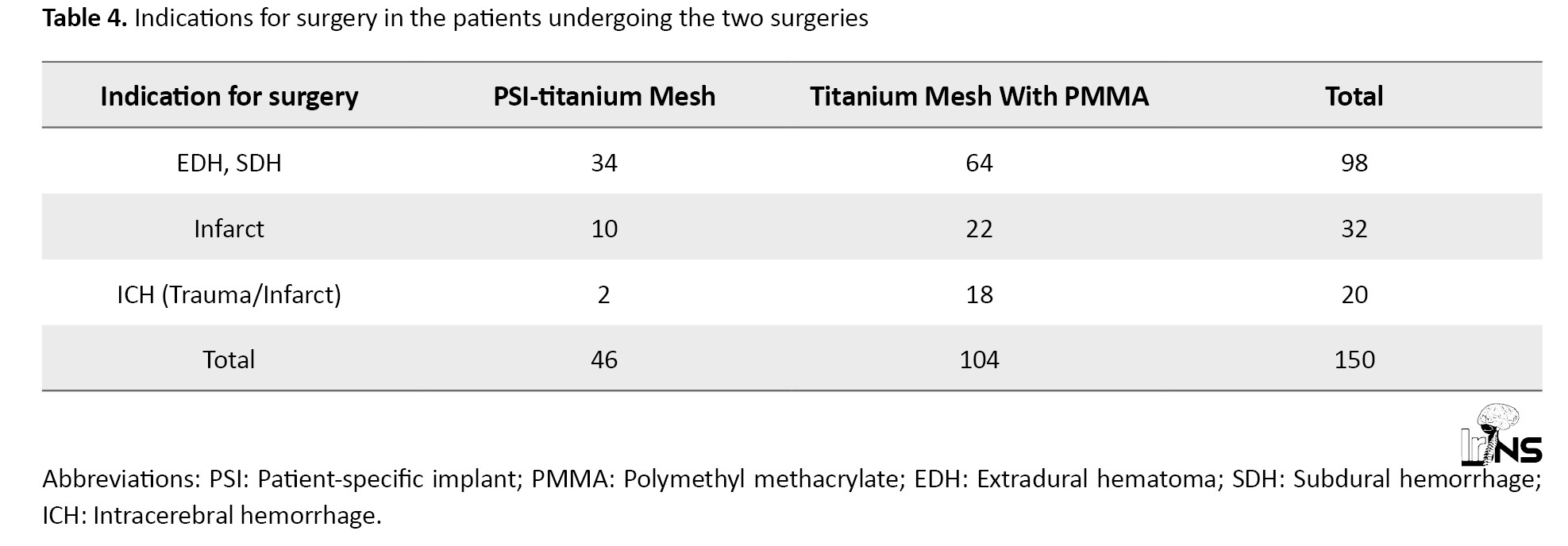

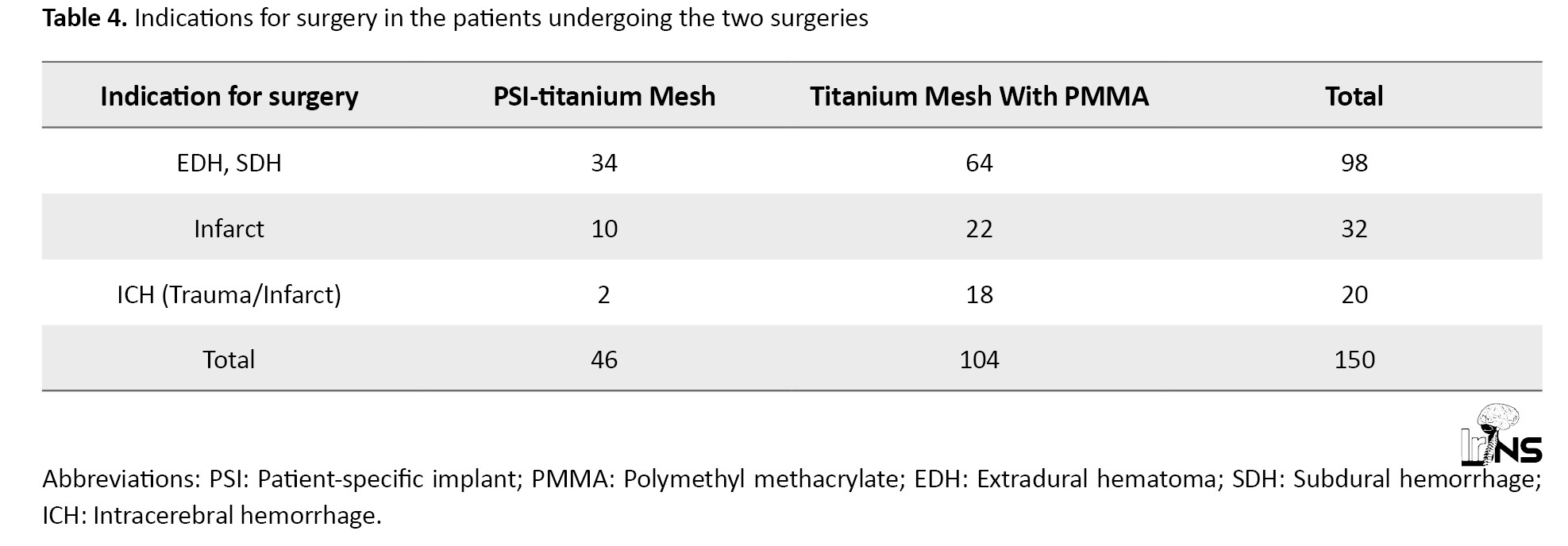

As per Table 4, the leading indication for decompressive craniectomy followed by cranioplasty for the patients in the study was extra-axial hemorrhage, with over 65% of patients, followed by infarcts (21%, both ischemic and hemorrhagic) and Intracerebral hemorrhage (13%).

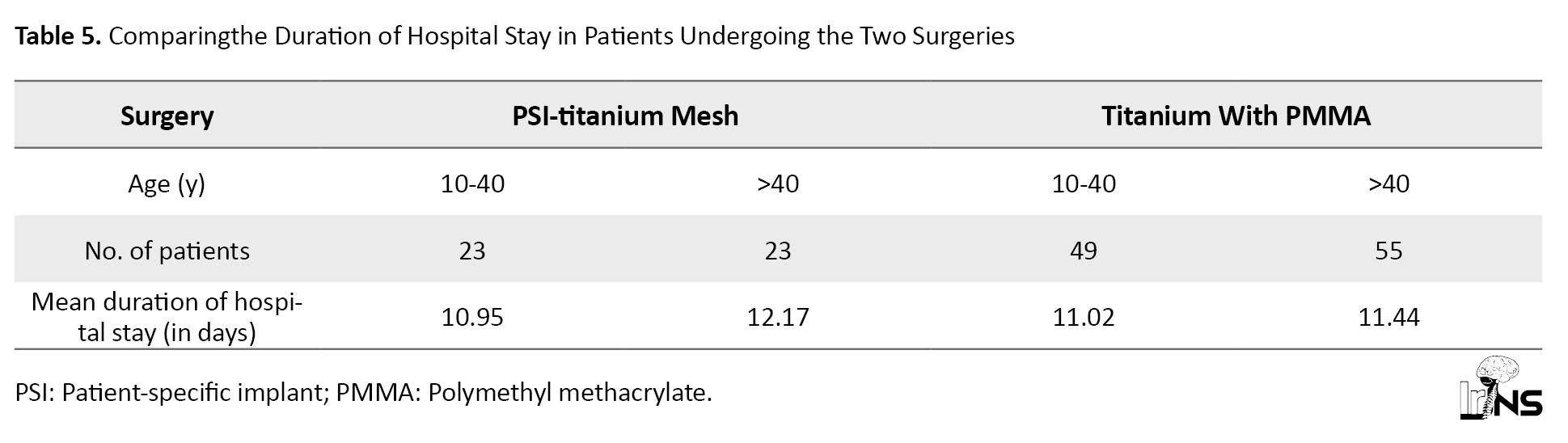

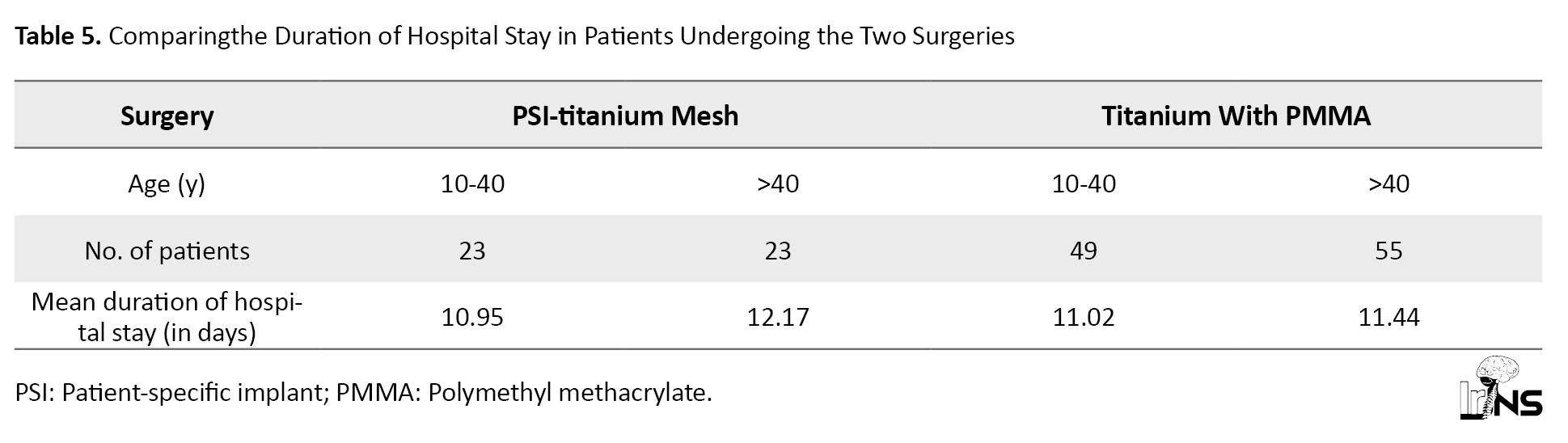

Our study shows no significant difference in hospital stay between the two surgeries (Table 5).

For ages 10-40, the t=-0.13323. The P=0.447196. The result is not significant at P<0.05. For ages >40 years, the t=1.34103. The P=0.091952. The result is not significant at P<0.05.

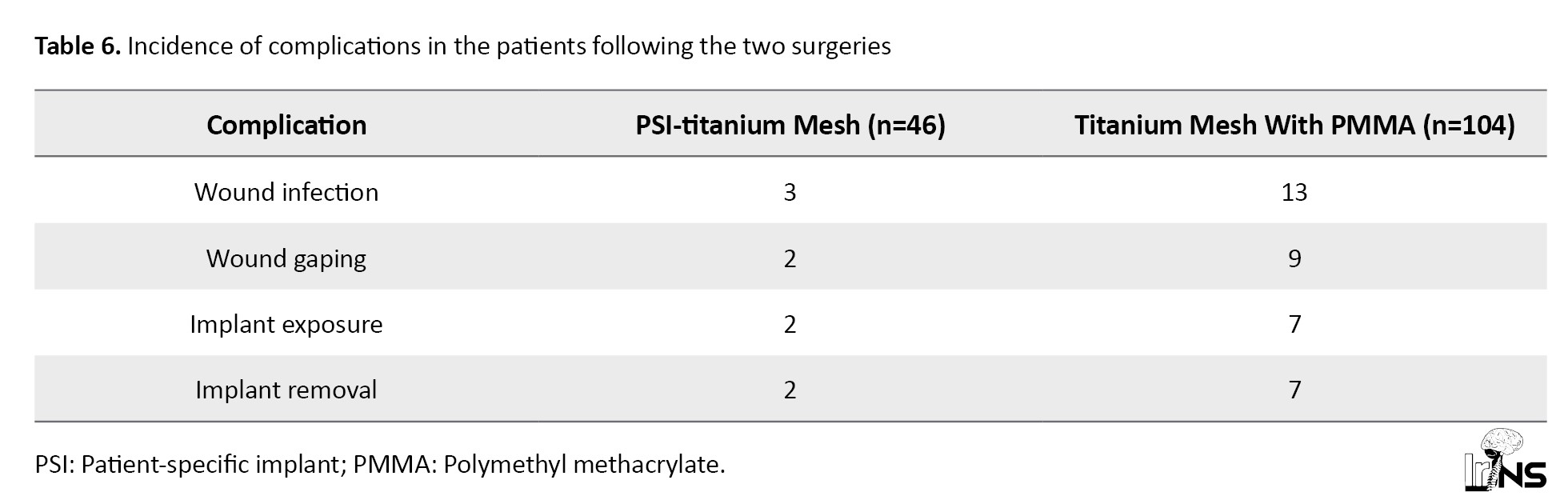

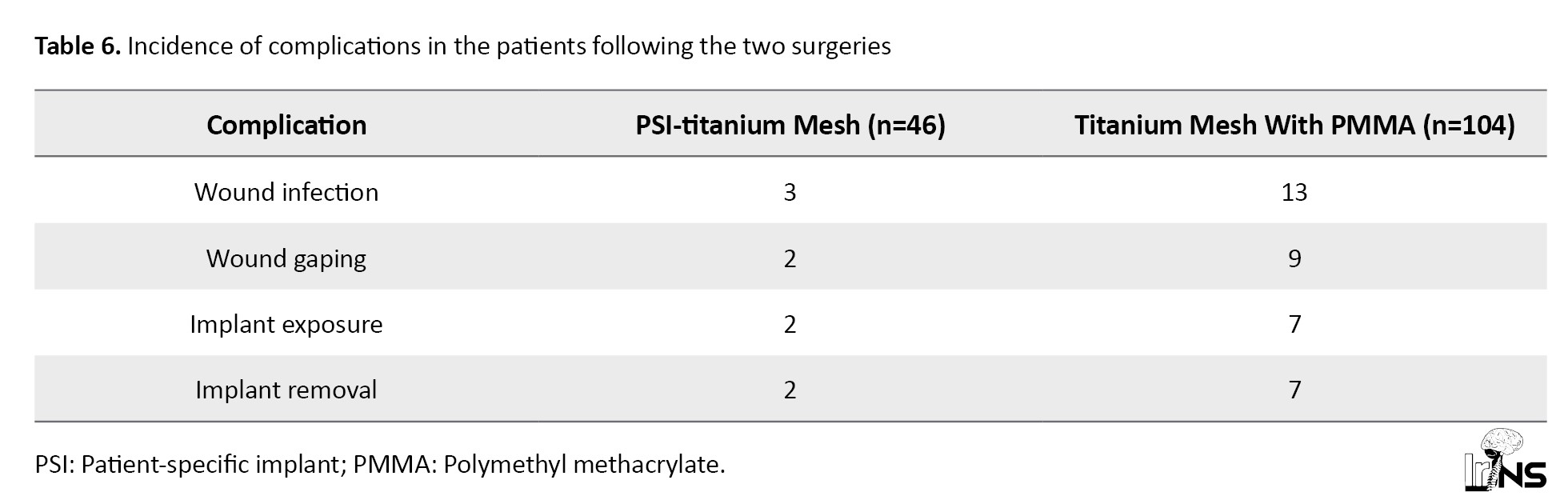

According to Table 6, Wound infection occurred in 6.5% of patients who underwent cranioplasty with a patient-specific implant (PSI)-titanium; none of the patients were under the age of 40.

Wound infection occurred in 12.5% of patients who underwent cranioplasty with titanium mesh+PMMA; 3 of the patients were aged 40 and below. Wound gaping occurred in 2 patients who underwent PSI-titanium cranioplasty (4.3%), one of whom was under the age of 40. On the other hand, 8.6% of patients who underwent cranioplasty with titanium mesh+PMMA developed wound gaping; 1 patient was under the age of 40. All patients who developed implant exposure following cranioplasty with titanium mesh and PMMA required implant removal (6.7%). Fourout of 7 patients were under the age of 40.

On the other hand, implant exposure occurred in 2 patients who underwent PSI Titanium; one of the patients consequently underwent implant removal. The different implant was removed due to a collection under the flap. Thus, the absolute incidence of complications is lower in PSI-titanium cranioplasty compared to titanium mesh with PMMA. Using the Fisher exact test, the p-value for the incidence of complications for both surgeries is 0.045, which is significant at P<0.05.

Patients whounderwent cranioplasty with a patient-specific titanium implant reported better cosmetic satisfaction when compared to patients whounderwent cranioplasty with a titanium mesh+PMMA implant.

4. Conclusion

Complications related to cranioplasty are common, as observed in our study. Patients who underwent cranioplasty with titanium mesh and PMMA showed a higher incidence of wound infection, wound gaping, implant exposure, and subsequent removal compared to those who underwent cranioplasty with a patient-specific titanium implant.

Patients who underwent cranioplasty with a patient-specific titanium implant have better cosmetic satisfaction than any other method of cranioplasty.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Coimbatore, India (Ref.No.: PSG/IHEC/2023/Appr/Exp/4pp Project.No. 23/452). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Funding

This research did not receive any grants or funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation: Jayaprakash Duraisamy and Rajkumar Pr; Drafting the manuscript, critically reviewing the final version of the manuscript, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declaredno conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jayaprakash Duraisamy and Rajkumar PR for their contribution in drafting the manuscript. The authors thank the facilities, faculties, and the management of PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Researchfor their support.

References

The occurrence of traumatic brain injury following road traffic accidents, assault, fall from height, and stroke (both hemorrhagic and ischemic) has become intensely common over the last two decades.

Monro-Kellie doctrine states that “the sum of all volumes of the brain, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and intracranial blood is constant”[1]. Following brain injury, this equilibrium is disrupted, resulting in increased intracranial pressure (ICP), which causes a decrease in cerebral blood flow due to a fall in cerebral perfusion pressure. To manage this damage, decompressive craniectomy was considered as an emergency life-saving procedure. The purpose is to reduce the raised ICP and to minimize the chances of brain ischemia [1, 2].

Decompressive craniectomy is a life-saving neurosurgical procedure done to relieve increased intracranial tension refractory to medical management [2]. This condition involves the removal of a wide portion of the skull bone to evacuate the brain hemorrhage (epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, or intracerebral hemorrhage)and to accommodate the brain swelling. The standard decompressive craniectomy includes the removal of a 15x12 cm bone flap in the fronto-temporo-parietal region (FTP) to reduce the mortality and to improve the neurological condition.

Indications and contraindications for cranioplasty

A few months after decompressive craniectomy, once the brain swelling settles, the new gradient between the atmospheric and ICP can result in neurological deterioration [2, 3].

In 1939, Grant and Norcross observed that after a few months of craniectomy, many patients developed severe headaches, altered cognitive behaviors, giddiness, and pain at the craniectomy site. It was later defined as Trephined syndrome [2].

The three main components of this condition include the occurrence of neurological deficits weeks to months after decompressive craniectomy, newly arising neurological deficits not associated with primary pathology, and clinical resolution after cranioplasty [2].

The neurological deficit that occurs a few months after craniectomy is called sunken flap syndrome, and if it restores with cranioplasty, it is taken as trephined syndrome. in clinical practice, however, the terms “sunken flap syndrome” and “trephined syndrome” are often used interchangeably.

Cranioplasty stabilizes the brain-atmospheric pressure difference and restores the physiology of the closed cavity, allowing the brain parenchyma to re-expand. The disturbance in CSF hydrodynamics and cerebral perfusion is well described in the chronic phase of decompressive craniectomy, and it is improved following cranioplasty [3].

Cranioplasty is done to reconstruct the skull 3-4 months after a decompressive craniectomy. This time gap is given for the brain to expand extracranially as a consequence of raised intracranial tension. This procedure holds a multitude of benefits. Besides protecting the brain parenchyma and cosmesis, it restores the physiology of the closed cavity, improves CSF dynamics, which is disrupted following craniectomy, as the atmospheric pressure exerts an influence on the brain and CSF [3]. This procedure also reduces the formation of pseudo-meningocele.

Meningitis, encephalitis, wound infection and sepsis, osteomyelitis, unmanaged post-traumatic hydrocephalus with brain herniation through the cranial cavity area few contraindications for cranioplasty.

Materials used

An ideal cranioplasty material should be inert, malleable, lightweight, readily incorporated with the existing skull bone, but not interfere with radiological imaging. Various materials have been used for cranial implants throughout history. Meekeren described the first documented evidence of cranioplasty using bone in 1668, when he repaired the skull of a Russian nobleman using the skull of a dead dog [4].

Moving forward to the 20th century showed the advent of homologous and autologous bone grafts. Autologous boneis the cheapest physiologic alternative to synthetic materials. Being the body’s tissue, it is viable, ie, has the potential to grow and does not fracture or get displaced easily [1, 5]. The main risk in using autologous bone includes infection, resorption, and flap collapse [5]. Another challenge in using autologous bone is the preservation of the graft between the time of removal and implantation. A common method of conservation is storing the autologous bone in the subcutaneous space of the abdomen and thigh. Cryopreservation at -70 °C has also been proven effective [6, 7].

Aluminum was the first metal to be used for making bone grafts, but it had high resorption rates and was known to reduce seizure threshold in patients [4, 8].

Silver and Gold were also used initially. However, they were expensive and their use was eventually discontinued [4]. Tantalum was an inert metal briefly used for cranioplasty during the early 1940s. [4, 8, 9]. Titanium was then used in place of Tantalum due to its low thermal conductivity and low radio-opacity.

Next, hydroxyapatite was used because it closely resembles human bone chemically. However, difficulty in contouring and the brittleness of hydroxyapatite rendered it practically obsolete [4, 8].

The interest then shifted to non-metals for grafting after seeing the success with dental implants. Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), discovered in 1940, is the most widely used prosthesis today. It is available in a powdered form, which, when mixed with benzoyl peroxide, produces an exothermic reaction followed by cooling. This process shapes the material to resemble the original bone. Despite giving excellent cosmetic results and making the radiological imaging process easier, PMMA did not integrate well with the surrounding tissue. It was prone to develop a fibrous coat over its surface, predisposing it to infections [1, 4, 10]. The intra-operative time was also longer due to the molding and cooling process.

One of the reasons why PSIs are so necessary is the immense diversity in the properties of each cranial bone, including its shape, thickness, andporosity. Each part of the same cranial bone also had different tensile strengths. Therefore, the type and design of the implant changes based on the anatomical location of the cranial defect. Initially, manufacturing craniofacial implants required a long, drawn-out process involving molding, casting, and extrusion, which offered fair accuracy but minimal cost benefits [11]. Later, 3D printing technologies developed, enabling neurosurgeons to manufacture PSIs using CT images to set the dimensions of the implant. This capability gave a lesser scope for error, shorter intra-operative time, and higher patient satisfaction [12].

Procedure

The procedure includes incision of the previous craniectomy scar, creation of a plane between dura mater and scalp, raising the scalp flap, raising the temporalis muscle flap, defining the bone defect all around, choosing the material for cranioplasty, fixing the cranioplasty material to the skull bone defect with titanium screws, placing a subgaleal drain, and suturing. Administering intraoperative anesthesia just before skin incision is widely adopted, but the frequency and duration of post-operative antibiotics are not clear.

2. Case Presentation

This research was a retrospective analysis study of the patients admitted to the neurosurgery ICU at PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Coimbatore, India, from January 2014 to January 2023.

Patients admitted with a previous history of FTP, decompressive craniectomy for traumatic brain injury (epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, or intracerebral hemorrhage), and for stroke (ischemic and hemorrhagic), with Glasgow coma scale (GCS) >13, skull defect >5 cm, and without surgical site infection were included in the study.

Patients who have undergone decompressive craniectomy for subdural empyema, brain abscess, Malignancies, GCS<13, and those who have surgical site infection were excluded from the study. Pediatric patients (<10 years) with decompressive craniectomy defects were also excluded from the study.

Computed tomography (CT) scans of the patient’s head post-decompressive craniectomy is done in our hospital; the necessary data is stored in digital imaging and communication in medicine (DICOM) format. These data are processed to create a virtual 3D patient model, after which titanium mesh is manufactured accordingly. Depending on the anatomical location of the cranial defect, the thickness of the mesh was between 0.3 mm and 0.6 mm. The mesh was sterilized under an autoclave before surgery.

3. Discussion

Of 150 patients admitted to the Neurosurgery ICU with decompressive craniectomy defects, 104 patients (69.3%) underwent cranioplasty with titanium mesh - PMMA implant, and 46 patients (30.7%) underwent cranioplasty with patient-specific titanium plate implant. Also, 75% of the patients were male, and 25% were female (Table 1).

About 48% of patients were between 10 and 40 years old, and 52% aged above 40 years (Table 2).

Table 3 highlights the various comorbidities of patients undergoing the study.

As per Table 4, the leading indication for decompressive craniectomy followed by cranioplasty for the patients in the study was extra-axial hemorrhage, with over 65% of patients, followed by infarcts (21%, both ischemic and hemorrhagic) and Intracerebral hemorrhage (13%).

Our study shows no significant difference in hospital stay between the two surgeries (Table 5).

For ages 10-40, the t=-0.13323. The P=0.447196. The result is not significant at P<0.05. For ages >40 years, the t=1.34103. The P=0.091952. The result is not significant at P<0.05.

According to Table 6, Wound infection occurred in 6.5% of patients who underwent cranioplasty with a patient-specific implant (PSI)-titanium; none of the patients were under the age of 40.

Wound infection occurred in 12.5% of patients who underwent cranioplasty with titanium mesh+PMMA; 3 of the patients were aged 40 and below. Wound gaping occurred in 2 patients who underwent PSI-titanium cranioplasty (4.3%), one of whom was under the age of 40. On the other hand, 8.6% of patients who underwent cranioplasty with titanium mesh+PMMA developed wound gaping; 1 patient was under the age of 40. All patients who developed implant exposure following cranioplasty with titanium mesh and PMMA required implant removal (6.7%). Fourout of 7 patients were under the age of 40.

On the other hand, implant exposure occurred in 2 patients who underwent PSI Titanium; one of the patients consequently underwent implant removal. The different implant was removed due to a collection under the flap. Thus, the absolute incidence of complications is lower in PSI-titanium cranioplasty compared to titanium mesh with PMMA. Using the Fisher exact test, the p-value for the incidence of complications for both surgeries is 0.045, which is significant at P<0.05.

Patients whounderwent cranioplasty with a patient-specific titanium implant reported better cosmetic satisfaction when compared to patients whounderwent cranioplasty with a titanium mesh+PMMA implant.

4. Conclusion

Complications related to cranioplasty are common, as observed in our study. Patients who underwent cranioplasty with titanium mesh and PMMA showed a higher incidence of wound infection, wound gaping, implant exposure, and subsequent removal compared to those who underwent cranioplasty with a patient-specific titanium implant.

Patients who underwent cranioplasty with a patient-specific titanium implant have better cosmetic satisfaction than any other method of cranioplasty.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Coimbatore, India (Ref.No.: PSG/IHEC/2023/Appr/Exp/4pp Project.No. 23/452). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Funding

This research did not receive any grants or funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation: Jayaprakash Duraisamy and Rajkumar Pr; Drafting the manuscript, critically reviewing the final version of the manuscript, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declaredno conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jayaprakash Duraisamy and Rajkumar PR for their contribution in drafting the manuscript. The authors thank the facilities, faculties, and the management of PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Researchfor their support.

References

- Winn HR. Youmans neurological surgery E-book. Edinburgh : Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011. [Link]

- Sarti TH, de Araújo Paz D, Diniz JM, Kim IH, Rodrigues TP, Cavalheiro S, et al. External cranioplasty for the syndrome of the trephined-case report. Interdisciplinary Neurosurgery. 2021; 24:101065. [DOI:10.1016/j.inat.2020.101065]

- Alkhaibary A, Alharbi A, Alnefaie N, Oqalaa Almubarak A, Aloraidi A, Khairy S. Cranioplasty: A comprehensive review of the history, materials, surgical aspects, and complications. World Neurosurgery. 2020; 139:445-52. [DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.211] [PMID]

- Shah AM, Jung H, Skirboll S. Materials used in cranioplasty: A history and analysis. Neurosurgical Focus. 2014; 36(4):E19. [DOI:10.3171/2014.2.FOCUS13561] [PMID]

- Celik H, Kurtulus A, Yildirim ME, Tekiner A, Erdem Y, Kantarci K, et al. The comparison of autologous bone, methyl-methacrylate, porous polyethylene, and titanium mesh in cranioplasty. Turk Neurosurgery. 2022; 32(5):841-4 [DOI:10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.37476-21.1]

- Shafiei M, Sourani A, Saboori M, Aminmansour B, Mahram S. Comparison of subcutaneous pocket with cryopreservation method for storing autologous bone flaps in developing surgical wound infection after Cranioplasty: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2021; 91:136-43. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocn.2021.06.042] [PMID]

- Rosinski CL, Chaker AN, Zakrzewski J, Geever B, Patel S, Chiu RG, et al. Autologous bone cranioplasty: A retrospective comparative analysis of frozen and subcutaneous bone flap storage methods. World Neurosurg. 2019; 131:e312-20. [DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.139] [PMID]

- Khader BA, Towler MR. Materials and techniques used in cranioplasty fixation: A review. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2016; 66:315-22. [DOI:10.1016/j.msec.2016.04.101] [PMID]

- Flanigan P, Kshettry VR, Benzel EC. World War II, tantalum, and the evolution of modern cranioplasty technique. Neurosurg Focus. 2014; 36(4):E22. [DOI:10.3171/2014.2.FOCUS13552] [PMID]

- Wang Q, Dong JF, Fang X, Chen Y. Application and modification of bone cement in vertebroplasty: A literature review. Joint Diseases and Related Surgery. 2022; 33(2):467-78. [DOI:10.52312/jdrs.2022.628] [PMID]

- Jindal S, Manzoor F, Haslam N, Mancuso E. 3D printed composite materials for craniofacial implants: current concepts, challenges and future directions. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2021; 112(3):635-53. [DOI:10.1007/s00170-020-06397-1]

- Schön SN, Skalicky N, Sharma N, Zumofen DW, Thieringer FM. 3D-printer-assisted patient-specific polymethyl methacrylate cranioplasty: A case series of 16 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2021; 148:e356-62. [DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.12.138] [PMID]

Type of Study: Case Series |

Subject:

Basic Neurosurgery

Send email to the article author

| Rights and Permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |